The California Gold Rush of 1849 taught investors a lesson that has echoed for nearly two centuries: don’t dig for gold; sell the shovels. In the artificial intelligence boom of the 2020s, the “gold” is the promise of AGI and automated productivity. But the definition of the “shovel” is currently being fought over in the stock market.

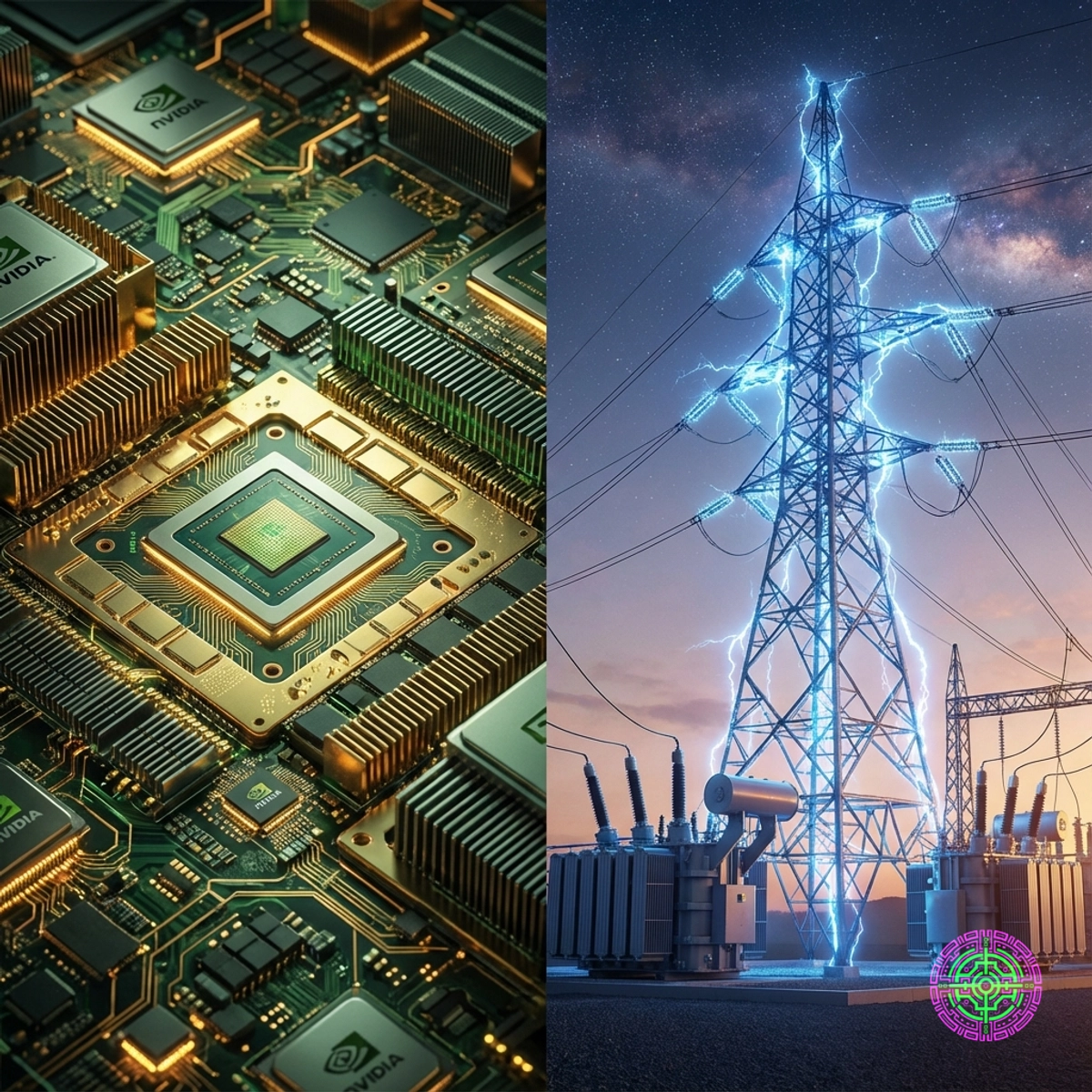

For the first half of this decade, the answer seemed obvious. Nvidia, the designer of the H100 and Blackwell GPUs, was the undisputed kingmaker. If a company wanted to train a model, it paid the “Jensen Tax.” But as 2025 closes, a new reality is setting in. The chips are available, but the electricity to run them is not.

While Nvidia has commanded headlines with its $3 trillion valuation, a quieter, century-old sector has begun to outperform the tech giant in specific annualized windows: the boring, regulated, dividend-paying electric utility.

This shift signals a fundamental change in the AI economy. The market is moving from a compute-constrained world to a power-constrained one. For investors and industry watchers, the question is no longer just who designs the best chip, but who can keep the lights on without melting the grid.

The First Shovel: The Nvidia Monopoly

To understand the scale of the energy problem, it is necessary to understand the sheer density of the compute being deployed. Nvidia is not just selling a chip. They are selling a new way of computing that is voraciously power-hungry.

The Margin King

Nvidia’s financial moat is arguably the widest in the history of hardware. In Q3 2025, the company reported revenue of $57 billion, a 62% year-over-year increase. More shockingly, they maintained gross margins north of 73%. In the hardware business, where 40% is considered excellent, this is nearly unheard of.

This profitability stems from their complete ecosystem lock-in. Their CUDA software platform acts as the operating system of AI. While competitors like AMD have made strides with their MI300 series, offering up to 25% better energy efficiency in some workloads, the switching costs for major labs remain prohibitively high.

The Physics of the H100

The dominance is physical. A single H100 GPU can consume up to 700 watts. A standard server rack in a traditional data center was designed to handle 5-10 kilowatts (kW). An Nvidia NVL72 rack, housing 72 Blackwell GPUs, pushes thermal design power (TDP) toward 120kW. This is not just a hotter computer. It is a fundamental breakage of legacy thermodynamics.

The Cooling Conundrum

Traditional data centers cool servers with air conditioning. Fans blow cold air over heat sinks. This works fine for 10kW. At 100kW, air is insufficient. The specific heat capacity of air is roughly 1.006 J/g°C. Water is 4.186 J/g°C. This is four times more efficient at carrying heat away.

To run an Nvidia Blackwell cluster, data center operators must rip out their air handlers and install Directed Liquid Cooling (DLC) loops. This piping brings cool liquid directly to the cold plate on the chip. It is complex, expensive, and heavy. Nvidia’s engineering challenge has shifted from “making chips smaller” to “managing the heat density of a star.” This physical reality forces a massive capital expenditure cycle for data centers, which plays directly into the hands of the energy providers.

The Second Shovel: The Energy Bottleneck

If Nvidia provides the engine, utilities provide the fuel. Right now, the fuel pump is running dry.

Goldman Sachs projects that data center power demand will grow 160% by 2030. For context, United States electricity demand has been effectively flat for two decades, growing at roughly 0.5% a year due to efficiency gains in appliances and lighting neutralizing population growth. AI has shattered that equilibrium.

The Utility Renaissance

Historically, utility stocks like Duke Energy, Southern Company, or Vistra were “widow-and-orphan” stocks: safe, slow, and defensive. In 2025, they became growth stocks.

Vistra (VST) and Constellation Energy (CEG) saw triple-digit gains, in some quarters significantly outpacing Nvidia. Why? Because they own the only asset that cannot be manufactured in a fab: reliable, baseload gigawatts.

The market has realized that a GPU can ship from Taiwan to Texas in 12 hours. Building a new transmission line in the United States takes 7 to 10 years. This mismatch has transferred pricing power from the chip buyer to the electron seller.

The 30MW vs. 300MW Problem

A standard cloud data center built in 2015 consumed about 30 megawatts (MW) of power. The “AI Factories” being permitted today are requesting 300MW to 500MW.

To put that in perspective, 500MW is roughly the output of a small nuclear reactor or a large coal plant. It is enough to power 400,000 homes. When a tech giant asks a local utility for that kind of connection, the answer is increasingly, “Get in line.”

The Regulatory Moat: The Queue from Hell

Nvidia’s primary constraint is TSMC’s CoWoS (Chip-on-Wafer-on-Substrate) packaging capacity. It is a manufacturing bottleneck that can be solved with money and new factories.

The Utilities face a regulatory bottleneck, which money cannot easily solve. In the United States, the “Interconnection Queue” (the waiting list for new power generation to connect to the grid) is currently backlogged with over 2,000 gigawatts of capacity, mostly solar and wind. The average wait time has exploded from <2 years in 2010 to >5 years in 2024.

This regulatory moat protects incumbent utilities. A startup cannot simply build a power plant and sell electricity to a data center. They need PJM, ERCOT, or CAISO approval. This entrenches the existing larger players who already have the transmission rights. For AI hyperscalers (Microsoft, Google, Amazon), this means they must partner with the incumbents. They have no choice but to pay the premium.

The Economics of Scarcity

The comparison between Nvidia and the Utilities reveals two different types of investment moats.

Nvidia’s Moat: Innovation and Ecosystem Nvidia wins because they run faster. Their 12-month release cadence (Hopper, Blackwell, Rubin) forces customers to upgrade or fall behind. However, this is inherently risky. If an inference model is developed that requires 90% less compute, or if a dedicated ASIC (Application Specific Integrated Circuit) takes share, Nvidia’s margins could compress rapidly. Their “shovel” is susceptible to being reinvented.

The Utility Moat: Regulation and Physics The utilities win because they are protected by the laws of physics and the government. Interconnection is mandatory. Even companies building behind-the-meter generation (like Amazon’s purchase of a nuclear-adjacent data center from Talen Energy) ultimately rely on grid interconnection for backup.

The scarcity here is absolute. There are only so many sites with access to water (for cooling) and high-voltage transmission lines. This physical scarcity has led to “power purchase agreements” (PPAs) being signed at substantial premiums. Utilities are effectively unregulated monopolies in their territories, and now they have a customer base with infinite pockets.

For Nvidia, demand is infinite, but scarcity is maintained by supply chain complexity. For Utilities, demand is rising, but scarcity is mandated by regulatory lag and construction timelines.

The Nuclear Option: SMRs and Briefcases

The energy constraint is so severe that it is forcing a technological pivot toward nuclear energy.

Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) are being touted as the solution. Companies like Oklo and NuScale are promising to deploy mini-reactors directly on data center sites. This effectively bypasses the grid bottleneck.

However, the timeline for SMRs is late 2020s at best. In the interim, specifically the next 3 to 5 years, the burden falls on existing generation. This is why the sector is seeing the “un-retirement” of coal plants and the life extension of aging nuclear facilities. The AI desire for clean energy is colliding with the reality of reliable energy. When the choice is “delay the model training” or “burn natural gas,” the tech giants are choosing the gas.

The Microsoft deal with Constellation Energy to restart Three Mile Island Unit 1 is the defining moment of this trend. Microsoft is effectively paying a 100% premium over market rates for 20 years just to guarantee 835MW of clean baseload power. This deal proves that for the hyperscalers, the cost of power is irrelevant compared to the cost of not having power.

Forward-Looking Analysis: Who Wins in 2030?

Looking toward the end of the decade, the balance of power between the chipmakers and the utilities will likely shift again.

Scenario A: The Efficiency Wall If hardware efficiency (performance per watt) outpaces model size growth, the energy crisis may be overstated. Nvidia’s Blackwell already offers significantly better efficiency than Hopper. If this trend accelerates, the utilities’ growth thesis might cool off.

Scenario B: The Jevons Paradox The more likely outcome is Jevons Paradox: as efficiency increases, consumption increases even more because the resource becomes cheaper to use. If inference becomes cheap, engineers will put it in everything, exploding total power demand.

In this scenario, the Utilities are the safer long-term bet. Nvidia faces competition from Google (TPU), Amazon (Trainium), and AMD. The Utility faces no competition for the delivery of electrons.

The “shovel” of 2024 was the H100. The “shovel” of 2026 is the gigawatt interconnect.

For the savvy investor, the play might not be choosing between them, but understanding the rotation. Nvidia provides the growth when the models are being built. Utilities provide the yield when the models are running. In the AI Gold Rush, the industry needs both the pickaxe to dig and the water to survive. But right now, the water is costing a lot more than anyone expected.

🦋 Discussion on Bluesky

Discuss on Bluesky