Editor’s Note (Feb 10, 2026): This article has been updated to reflect corrected wattage figures (250W) based on community feedback and further verification. We originally published with the 650W general estimate, but have adjusted all calculations to match the specific Rivian R1T hardware specifications rather than theoretical maximums.

The dream of the “infinite range” electric vehicle has largely been a graveyard of ambition. From the cancellation of the Sono Sion to the financial collapse of Lightyear and the struggles of Fisker, integrating solar panels directly into vehicle bodywork has proven too expensive and structurally complex for mass production. These projects failed not because the idea was bad, but because the execution required reinventing the entire automobile.

But what if the solar array wasn’t the car, but an accessory?

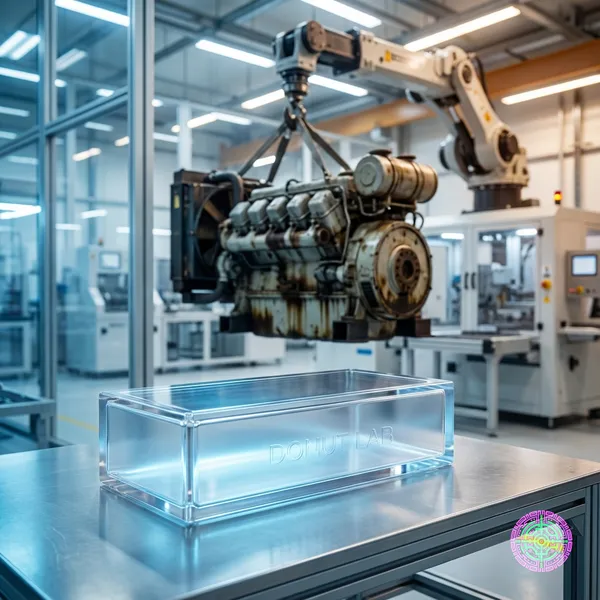

Worksport, a manufacturer known for truck bed covers, has announced the Solis Solar Tonneau Cover is finally widely available for the Rivian R1T, with shipments beginning in January 2026. By decoupling the power generation from the vehicle’s chassis, Worksport is attempting to solve the solar equation with a modular approach.

For Rivian owners, a demographic that heavily skews towards overlanding and off-grid camping, this promises a new level of energy independence. The promise is enticing: park your truck in the sun and let it refuel itself. But before buyers expect to drive across the continent on sunlight alone, a rigorous look at the physics is necessary.

The Hardware: 250 Watts of Potential

The Solis system is not just a passive cover; it is active power generation infrastructure. The engineering specifications reveal a system designed for high output within a constrained footprint.

- Peak Output: Approx. 250W (under ideal STC conditions).

- Storage: Integrates with the COR Mobile Energy System, a modular portable battery generator (typically 1-6 kWh capacity).

- Construction: Folding proprietary solar panels ruggedized for impact resistance.

Unlike the “SolarSky” roof on the Fisker Ocean, which was permanently bonded to the vehicle, the Solis is a tonneau cover. It sits flat on the bed, utilizing a much larger surface area (roughly 2.5 square meters) compared to the roof of a standard SUV, which typically offers less than 1.5 square meters of usable solar real estate.

The Physics of Flat Solar: The Cosine Loss Problem

While 250W is the headline number, real-world performance will be dictated by geometry. Solar panels perform best when maximizing the angle of incidence—ideally pointing directly at the sun. A tonneau cover, by definition, is flat.

Unless the truck is parked on a significant incline facing south, the “Angle of Incidence” () will rarely be zero. The power output () is roughly proportional to the cosine of this angle:

In mid-latitudes during winter, the sun might only reach an elevation of 30 degrees. This means the light is hitting the panels at a shallow 60-degree angle from the normal.

In this scenario, the 250W array would theoretically output only 125W, even in clear skies. This “Cosine Loss” is the primary reason why solar on vehicles has historically underperformed marketing claims. Worksport mitigates this by using high-efficiency monocrystalline cells, but they cannot cheat physics. Users should expect peak output only near solar noon in summer months.

The Mathematics of Propaganda: Driving vs. Camping

Why have previous solar cars failed? The math of propulsion is brutal. To understand the value proposition of the Solis, one must separate “range anxiety” from “camp anxiety.”

A Rivian R1T consumes roughly 430 Wh per mile (conservative estimate with off-road tires and gear). One hour of sunlight at peak 250W generation produces 250 Wh of energy.

In a best-case scenario (six hours of perfect, uninterrupted sunlight) you gain about 3-4 miles of range. If a buyer is looking for a range extender to bypass charging stations, this is negligible. It would take weeks to recharge the massive 135 kWh Large Pack.

However, the equation flips when the vehicle stops moving.

For an overlander, energy is currency. When off-grid, the truck is no longer a vehicle; it is a stationary habitat.

- 12V DC Fridge: Draws 40-50W average.

- Starlink Terminal: Draws 50-75W.

- LED Camp Lights: Draw 20W.

- Laptop Charging: Draws 60W intermittently.

With a 250W intake (or even 150W real-world average), the Solis can significantly offset this load, actively recharging the auxiliary batteries while the equipment is running. In this context, the Solis isn’t a “range extender” for the truck, but it is a powerful run-time extender for base camp.

Contextual History: Why Accessories Succeed Where Cars Failed

The history of solar EVs is a lesson in integration hell. The graveyard is full of companies that tried to marry solar cells to chassis manufacturing.

- Sono Sion: This startup attempted to wrap an entire hatchback in polymer-based solar cells. The result was a manufacturing nightmare that made standard body repairs impossible. If a fender bender occurred, the owner wasn’t just fixing a dent; they were replacing a complex electrical component. The company successfully validated the tech but failed to fund the production line.

- Lightyear 0: Lightyear achieved remarkable efficiency but at a price point of roughly €250,000. The solar yield was real (up to 70km/day in Spain), but the cost per watt was astronomical.

- Cybertruck: Tesla promised a solar tonneau cover in 2019. As of late 2025, it remains unreleased, with aftermarket solutions like Worksport filling the gap.

Accessories like the Solis succeed because they do not interfere with the vehicle’s homologation or safety crash structures. They are “add-ons,” bypassing the regulatory hurdles that strangled Sono and Lightyear. If the Solis cover breaks, you replace the cover. If the Sono Sion door broke, you had to source a proprietary solar-integrated body panel.

The Integration Barrier: Why Can’t It Charge the Truck Directly?

The most common question potential buyers ask is: “Does it plug into the charge port?”

The answer highlights a major technical hurdle in EV modification. The Rivian R1T, like all modern EVs, has a complex high-voltage (HV) architecture managed by a Battery Management System (BMS). The J1772 charge port expects an AC signal which the onboard charger converts to DC.

To feed solar power (DC) into the main battery, the system must either:

- Invert to AC: Convert the solar DC to AC, then feed it into the charge port, where the car converts it back to DC. This “Double Conversion” incurs efficiency losses of 15-20%.

- DC Injection: Safely splice into the HV DC bus. This is technically perilous and would immediately void the vehicle warranty.

Worksport has designed the Solis to feed the COR Mobile Energy System primarily. This is an external battery bank. While this feels like a compromise, it is actually the most efficient path. By using the solar array to charge a secondary battery which runs the camp amenities (fridge, lights, stove), the user avoids drawing power from the main traction battery.

The “Vampire Drain” Mitigation Strategy

Rivian owners are famously plagued by “Vampire Drain”: the loss of 1-3% of battery per day while parked, due to systems like Gear Guard and connectivity features failing to sleep.

A 1% loss on a 135 kWh pack is roughly 1.35 kWh per day.

A 250W solar cover, generating effectively for 5 hours, produces 1.25 kWh.

Even with conversion losses, the Solis can largely offset the vampire drain in decent solar conditions. For long-term parking at an airport or trailhead, this transforms the vehicle from a degrading asset into a stasis pod. The truck effectively hibernates with minimal net energy loss, ensuring that the range you parked with is the range you return to.

Economic Analysis: Is It Worth $2,000?

The estimated price point of $2,000+ places the Solis in a premium category. How does it compare to the alternatives?

- Gas Generator (Honda EU2200i): Costs $1,100. Requires fuel, noise, maintenance.

- Portable Solar Panels (400W): Cost $600-$800. Require setup time, occupy cargo space, cannot charge while driving.

- Worksport Solis: Costs $1,999 (plus ~$949 for battery system). Zero setup, zero storage space lost, charges passively.

The value is not in the “electricity saved” (which might only amount to $50 per year). The value is in the workflow. The friction of setting up portable panels often leads users to not use them. The Solis is “always on.” For the serious overlander, removing the chore of “deploying solar” is worth the premium.

The Future Outlook

The launch of the Solis for the R1T validates a shift in the market. As EV batteries get larger (Rivian Max Pack is 149 kWh), the idea of “solar charging the car” for propulsion becomes less mathematically viable. The surface area of the car simply cannot capture enough photons to fill the bucket significantly.

However, as mobile power stations, EVs are rapidly replacing gas generators. The Worksport Solis represents the logical accessory for this transition: a silent, fuel-free way to keep the lights on without draining the tank.

For the weekend warrior, paying premium prices for a solar cover might never pay off in strictly monetary terms. But for the remote explorer, 250W of power in the middle of the Utah desert is not about ROI in dollars. It is about the ROI of silence, independence, and the assurance that no matter how long you stay, the lights will stay on.

🦋 Discussion on Bluesky

Discuss on Bluesky