The Argument in Brief

The “Transition” is over before it truly began. For the last 18 months, the automotive industry has rallied around a single, expensive buzzword: Extended Range Electric Vehicles (EREV). Companies like Stellantis and Ford have bet billions that the market isn’t ready for a pure Electric Vehicle (EV), and that a decade-long “bridge” of gas-engine generators is needed to solve range anxiety.

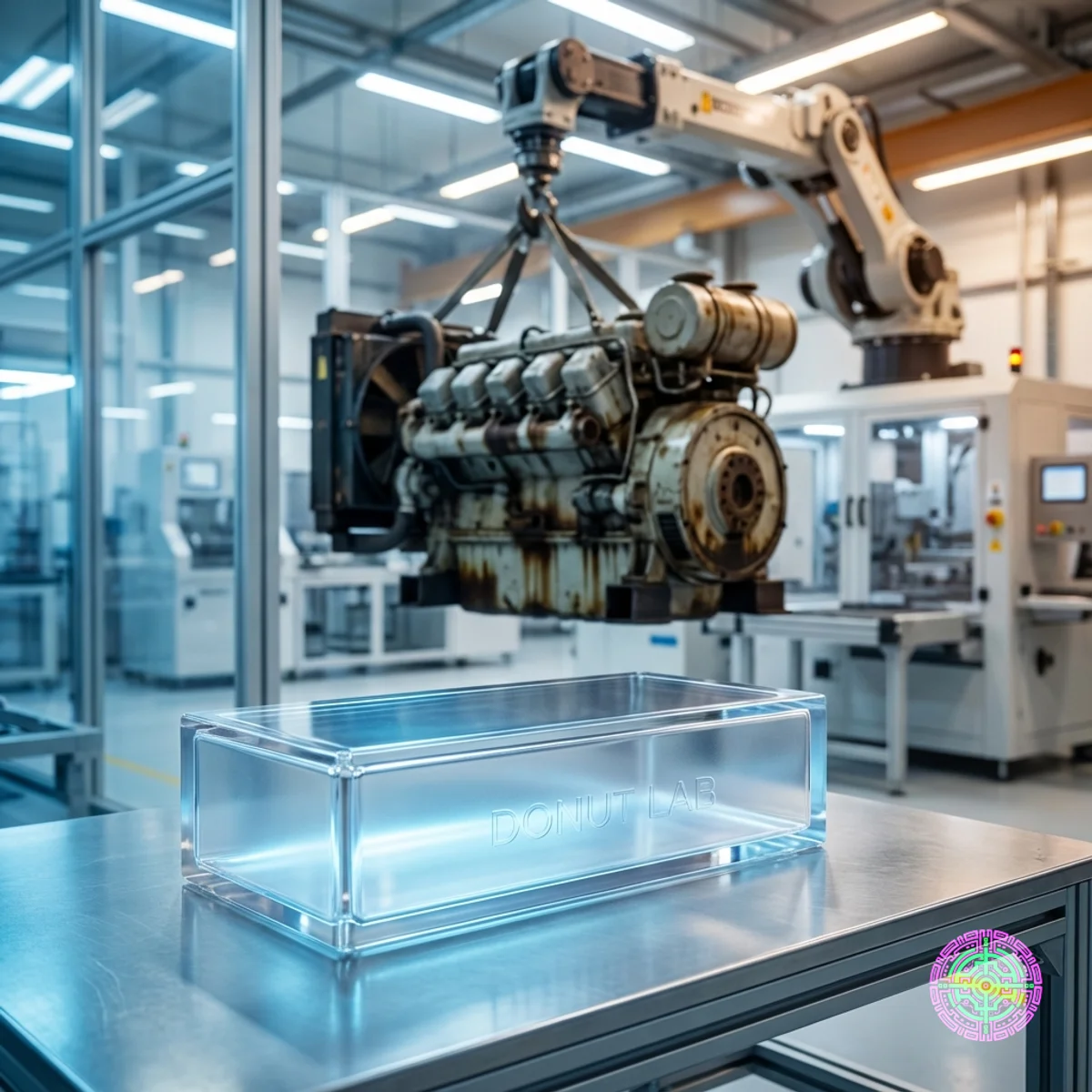

On January 5, 2026, a small Finnish startup named Donut Lab lit that bridge on fire. By showcasing a production-ready, 400 Wh/kg solid-state battery (SSB) on the floor of CES, the company didn’t just improve the bike: it destroyed the mathematical justification for the hybrid generator. If 600 kilometers of range is achievable in a 10-minute charge with a “safe” ceramic battery, the gas-powered range extender isn’t a bridge; it’s a legacy anchor dragging down the future of mobility.

The Conventional Wisdom

The prevailing narrative in Detroit and Wolfsburg throughout late 2025 was one of “Pragmatic Realism.” As EV sales growth slowed, the industry pivoted. The consensus was that “Pure EV” was too early for the mass market because of two insurmountable walls: Range Anxiety and Charging Velocity.

The solution was the EREV. A vehicle like the Ramcharger, which carries a massive lithium battery but keeps a 130 kW gas engine solely to act as a mobile generator. The idea was to give the “feel” of an EV with the “security” of a gas tank. Stellantis doubled down on this in early January 2026 with a $13 billion U.S. investment plan centered on multi-energy platforms. The industry assumed a middle-ground for at least another ten years while waiting for the “Solid-State Holy Grail.”

Why the Consensus is Wrong

The “Holy Grail” isn’t a research project anymore; it’s a shipping product. Donut Lab’s arrival at CES with a battery that is effectively double the density of the best liquid-electrolyte cells changes the fundamental weight-to-range equation. When the battery is twice as light for the same power, the space formerly occupied by a heavy 4-cylinder range extender, a fuel tank, and an exhaust system can simply be filled with more battery.

Point 1: The Weight Penalty Math

Automotive engineering is a zero-sum game of mass. In a traditional EREV, a vehicle carries around 200kg to 300kg of “just in case” machinery: the gas engine, the generator, and the fuel. That machinery is useless 95% of the time, yet the cost is paid in every mile of efficiency.

With Donut Lab’s 400 Wh/kg density, that 250kg of gas equipment can be replaced with enough solid-state energy to drive an extra 400 kilometers. This results in a vehicle that has the same total range as the hybrid, but is lighter, simpler, more reliable, and has zero oil changes.

Point 2: The Charging Velocity Factor

The EREV’s secondary purpose was to solve the “45-minute wait” at charging stations. Donut Lab’s CES demo showed 80% charge in 10 minutes at 200 kW without the need for complex thermal preconditioning. This is the “Gas Station Parity” moment. If a battery can “refill” in the time it takes to buy a cup of coffee, the entire logic of carrying a portable gasoline power plant disappears.

Point 3: The Infrastructure Fallacy

Critics argue that charging infrastructure isn’t ready. But the $13 billion Stellantis just threw at a “balanced” U.S. strategy could build 65,000 high-speed charging stalls. Legacy automakers are spending tens of billions on the complexity of dual powertrains rather than the simplicity of a universal charging grid. The industry is building the “bridge” because companies are too terrified to build the road.

The Evidence

The evidence that the EREV is a strategic dead end comes from the hardware already hitting the pavement in Q1 2026.

[The Hardware Proof]: The Verge TS Pro motorcycle serves as the technical vindication. In 2023, critics said Donut Lab’s hollow-core motors were “vaporware.” By 2025, they were the benchmark for the industry (See the look at the Axial Flux Revolution). Now, Verge is shipping the TS Pro with a 370-mile (600 km) range. For a motorcycle: a segment traditionally crippled by the weight of batteries: this is a localized miracle. If it works on two wheels, it’s only a packaging problem for four.

[The Thermal Stability Proof]: One of the biggest hurdles for EREVs was the “Cold Weather Penalty.” Liquid batteries lose 30-40% of their range in a Michigan winter, forcing the gas engine to kick in just for heat. Donut Lab’s solid-state chemistry retains over 99% capacity at -30°C. It removes the environmental reason to keep a combustion engine in the loop.

[The Safety Proof]: Solid-state batteries are non-flammable. By removing the “liquid fire” (electrolyte) and the “liquid fire” (gasoline), the insurance and regulatory burden for these vehicles drops significantly. Insurers are already questioning the dual-risk profile of EREVs that combine high-voltage packs with pressurized fuel systems.

The Counterarguments

”Solid-State is still too expensive for the mass market.”

Analysis: In Q1 2026, there is no denying the initial capital premium. While Donut Lab has avoided expensive rare-earths, the precision required for ceramic electrolyte manufacturing still commands a significant markup over liquid-electrolyte China-made LFP cells. However, for a manufacturer, this cost is not viewed in isolation; it is a total system balance.

By removing the engine, the multi-stage transmission, the secondary cooling loops for the ICE, and the high-pressure fuel system, manufacturers claw back thousands of dollars in bill-of-materials (BOM) cost and assembly-line hours. While the raw Battery Pack cost is higher, the Total Vehicle Cost for a 600-mile pure SSB truck can potentially match the price of a heavy, complex EREV counterpart. You are paying for cells instead of pistons.

”The industry lacks the material to build millions of these.”

Analysis: This is a legitimate concern, but it applies to the “Bridge” strategy too. EREVs still need Lithium, Nickel, and Cobalt. Donut Lab claims to use “abundant, geopolitically safe materials,” but the industry is currently reeling from China’s December 2025 silver export license mandate. Since high-performance SSBs often rely on silver-based electrolytes (See: The Silver Export Crisis), the bottleneck isn’t the technology; it’s the geography.

A Real-World Example: The “Scout” Split

Look at the divergence in strategy for 2026. Scout Motors (VW’s rebirth) is building a $2 billion plant in South Carolina for a pure-electric platform from the ground up (See the Scout Analysis). The bet is that by the time full capacity is reached in 2027, the “Pure EV” physics will have won.

Meanwhile, Stellantis is spending part of its $13 billion U.S. war chest to keep the internal combustion engine on life support via the Ramcharger. History teaches that when a manufacturer tries to please everyone (the gas enthusiasts and the EV adopters), the result is usually a vehicle that is heavy, expensive, and a compromise for both.

What This Really Means

For Consumers

Stop buying the “Hybrid is the only realistic option” narrative. For those in the market for a high-end truck or performance car in 2026, the technology is about to be leapfrogged by solid-state hardware that makes a “Range Extender” look like a steam engine.

For Companies

Ford and Stellantis are currently in a high-stakes game of “Sunk Cost.” They have thousands of employees and billions in assets dedicated to the combustion engine. Donut Lab’s CES announcement is a klaxon horn: the “Pragmatic Bridge” has no landing zone.

For the Industry

The “Two-Tiered EV Future” discussed previously—where luxury buyers get the range and everyone else gets the “poverty pack” (See: The Luxury Lock-in)—is about to accelerate. Donut Lab’s tech will hit the $100,000 trucks first, making the “bridge” EREVs look even more antiquated by comparison.

This isn’t just about batteries; it’s about the end of the Complexity Era. For a hundred years, cars were improved by adding more parts: valves, turbos, sensors, hybrids. Donut Lab represents the Subtraction Era. Removing the liquid, removing the fire, removing the preheating, and ultimately, removing the gas engine. The companies that can’t learn to subtract will be buried by those who can.

Future Outlook

- Watch the Silver Prices: If the silver supply chain remains under Chinese control, Donut Lab’s disruption will be limited to premium “Halo” bikes like the Verge TS Pro.

- The “Ford Pivot” Retraction: Look for Ford to quietly scale back hybrid-heavy messaging by mid-2026 as SSB yield rates improve.

- The Second-Hand Cliff: Watch the resale value of early 2025/2026 EREVs. As pure-SSB vehicles prove their 100,000-cycle durability, the “Dual-Maintenance nightmare” of the hybrid will lead to a secondary market collapse.

The Uncomfortable Truth

The “Pragmatic Middle Ground” was a myth maintained because the industry wasn’t ready to let go of the gas pump. Automakers didn’t build EREVs because they were better; they built them because they were easier to manufacture than a perfect solid-state cell. Now that Donut Lab has proven the “impossible” is shipping, “easy” is no longer an excuse.

Final Thoughts

The industry previously claimed solid-state was ten years away. Then it was five years away. Then “Maybe by 2030.”

At CES 2026, Donut Lab stopped talking and started shipping. The “Bridge” that Detroit spent billions building now leads directly into a 400 Wh/kg brick wall. The time has come to stop building bridges and start building the future.

Sources

- Supercar Blondie: Phone-sized solid-state battery already powering production EV

- Electrek: Verge unveils 370-mile electric motorcycle with solid-state battery

- Stellantis Unveils Massive $13 Billion U.S. Investment

- Resource World: Silver’s Stunning 2025 Rally Meets a New Era of Chinese Control

- Verge Motorcycles switches to in-house solid-state batteries

🦋 Discussion on Bluesky

Discuss on Bluesky