Key Takeaways

- The Shift: The industry is moving from “Computer-Aided Design” (CAD), where humans draw lines, to “Computer-Generated Design,” where humans set goals and AI draws the geometry.

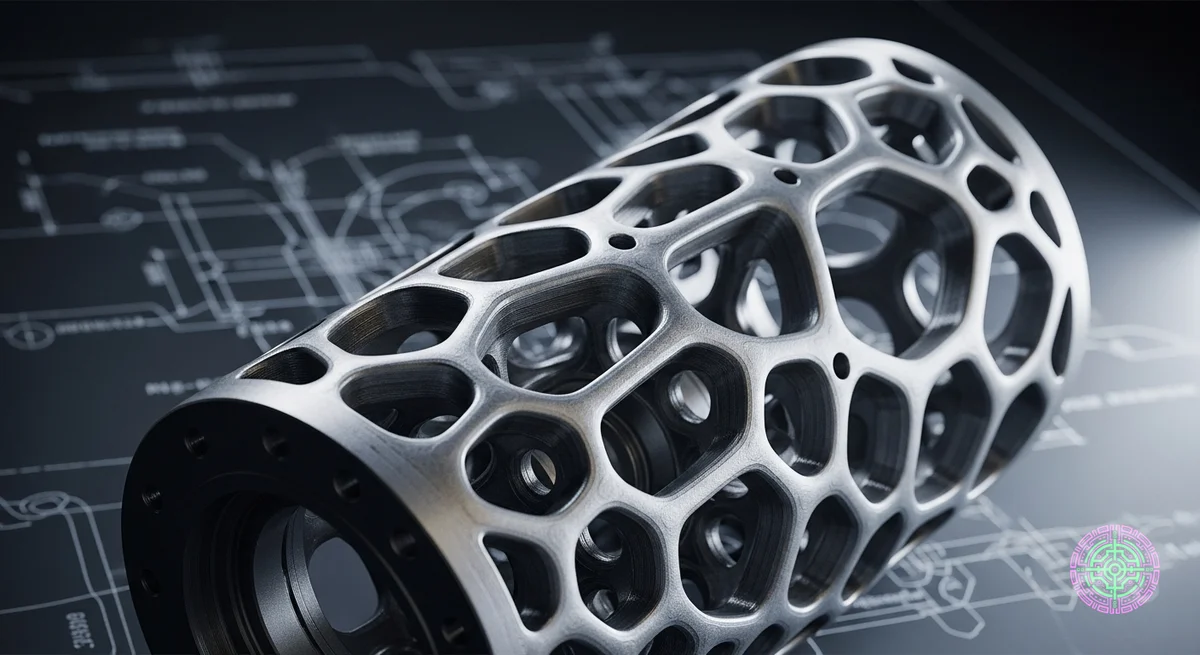

- The Look: The resulting structures often look “alien” or “organic”:resembling bone lattices or tree roots:because nature and physics share the same optimization logic.

- The Physics: It works by combining Finite Element Method (FEM) simulation with iterative modification. The AI removes material from low-stress areas and adds it to high-stress areas.

- Impact: Companies like Airbus and GM are seeing 40% weight reductions with zero loss in strength, critical for EV range and space travel logic.

If you look at the chassis of the latest high-performance electric vehicles or the landing legs of a new SpaceX rocket, you might notice something unsettling.

They don’t look like they were built by humans.

Straight lines and perfect circles:the hallmarks of human engineering for 5,000 years:are disappearing. In their place are twisting, organic curves, hollowed-out bones, and intricate lattices that look more like they were grown in a petri dish than stamped in a factory.

This isn’t an aesthetic choice. It’s Generative Engineering.

For the first time in history, engineers aren’t telling the computer what to draw. They are telling it what they need:“Make a bracket that holds 500kg, fits in this box, and weighs as little as possible”:and the AI is solving the physics problem itself.

The Physics of “Hallucinating” Structure

To understand how an AI “grows” a metal bracket, you have to understand the optimization loop. It’s a brutal game of trial and error played at the speed of light.

1. The Design Space

The engineer defines a “block” of material:the maximum space the part operates in. They also define the “Loads” (forces) and “Boundary Conditions” (where it bolts on).

2. Finite Element Analysis (FEA)

The computer breaks the block into millions of tiny cubes (elements). It simulates the forces.

- Red Zones: Areas under high stress.

- Blue Zones: Areas doing no work.

3. Topology Optimization

This is the “generative” part. The algorithm acts like a sculptor. It looks at the “Blue Zones”:the lazy material that isn’t carrying load:and deletes it. It then runs the physics simulation again.

It repeats this process thousands of times.

- Iteration 1: Remove 5% of useless material.

- Iteration 100: The block looks like Swiss cheese.

- Iteration 1000: The shape resolves into a perfect, organic tendon.

The AI essentially “evolves” the part. Just as millions of years of evolution stripped the human femur down to its most efficient form (dense on the outside, spongey lattice on the inside), the AI strips the bracket down to its mathematical necessity.

Why “Organic” Shapes?

Why do AI designs look like bones? Because biology is the ultimate engineer.

- Stress Dispersion: Sharp corners concentrate stress (the “stress riser” effect), leading to cracks. Nature avoids sharp corners. AI, following the path of least resistance, rounds everything off into flowing curves that distribute loads evenly.

- Hierarchical Structures: Trees are solid trunks, branching into limbs, branching into twigs. AI uses “Lattices”:micro-structures that mimic this hierarchy:to create parts that are solid where they need to be and mostly air where they don’t.

Case Studies: AI in the Wild

1. Aerospace: The Airbus Partition

Airbus used generative design to recreate the partition that separates the cabin from the galley.

- Old Design: Heavy, solid wall.

- AI Design: A “bionic” web that looks like slime mold.

- Result: 45% weight reduction. In aviation, shedding 30kg translates to thousands of tons of saved jet fuel over the plane’s life.

2. Automotive: The EV Range War

General Motors used the tech to redesign a simple seat bracket.

- Old Design: 8 separate steel parts welded together.

- AI Design: 1 single 3D-printed stainless steel part.

- Result: 40% lighter and 20% stronger. For EVs, every gram saved is free range. Entire chassis components are now being “grown” by AI to shave off 20-30% of the weight without sacrificing strength. BMW and GM are already using these organic-looking brackets in production cars.

Challenges & Limitations

If this is so great, why isn’t every part “grown”?

- Manufacturing Hell: You can’t stamp these shapes. You can’t mill them easily. Often, the only way to build a generative design is 3D Printing (Additive Manufacturing). This is slow and expensive compared to mass casting.

- The “Black Box” Problem: Engineers trust math, but they verify with intuition. When an AI hands you a twisting, alien shape and says “Trust me, it holds,” conservative industries (like nuclear or civil engineering) are hesitant to sign off without months of testing.

- Cost of Compute: Running thousands of FEA simulations for a single bracket requires massive GPU power.

What’s Next?

Short-Term (2026)

“Manufacturability Constraints”. The new wave of AI tools (like Autodesk Fusion) understands physics and factories. You can tell the AI, “make this for a 3-axis CNC mill,” and it will only generate shapes that can actually be cut by that machine.

Long-Term (2030+)

“Generative Materials”. Engineers won’t just generate the shape; they will generate the matter. AI is discovering new metamaterials (micro-lattices) that are lighter than cork but stronger than steel.

The Bottom Line

Generative Engineering is the death of the straight line.

For centuries, humans built boxy houses and blocky cars because those were the shapes the human brain could calculate and human hands could draw. But nature doesn’t build in boxes; it builds in webs, curves, and lattices.

With AI acting as the translator, engineers are finally learning to speak the language of nature. And the things they build will never look the same again.

🦋 Discussion on Bluesky

Discuss on Bluesky