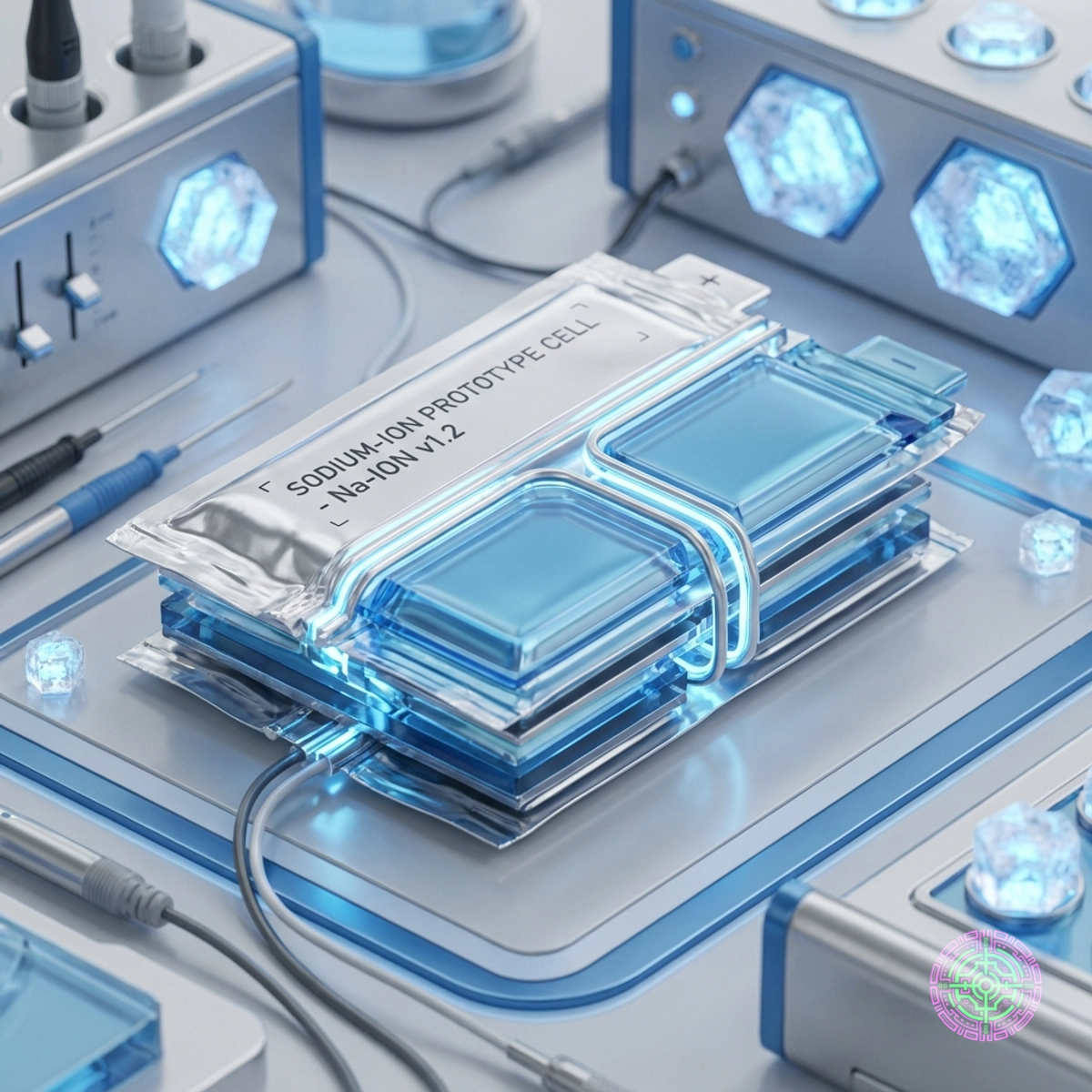

On December 18, 2025, a quiet announcement from a European laboratory signaled the end of an era. While the headlines were dominated by the latest EV price wars and lithium mining disputes, a consortium of researchers and manufacturers confirmed the production of Europe’s first sodium-ion battery cell made entirely from domestic components.

There was no lithium from Chile. No cobalt from the Congo. No graphite from China.

Instead, the cell was built using hard carbon derived from European wood industry byproducts and sodium sourced from common salt. For a continent that has spent the last decade swapping dependence on Russian gas for dependence on Chinese batteries, this isn’t just a scientific curiosity. It is a geopolitical lifeline.

This is the promise of the “Salt Revolution”: a battery that sacrifices a small amount of range for total supply chain immunity. As winter grips the continent and EV drivers struggle with range loss, the timing couldn’t be more potent. Sodium-ion chemistry doesn’t just bypass the lithium supply chain; it laughs at the cold.

The Chemistry of Independence

To understand why this specific cell is a breakthrough, you have to look at the anode. In a lithium-ion battery, the anode is almost always graphite. The lithium ions slide comfortably between the layers of graphite in a process called intercalation.

But sodium ions are different. They are the heavier, clumsier cousins of lithium.

The Geometric Problem

A sodium ion () has an ionic radius of roughly 1.02 Å (Angstroms), significantly larger than a lithium ion’s 0.76 Å. If you try to force a sodium ion into a standard graphite lattice, it’s like trying to park a Hummer in a compact space. It physically doesn’t fit. The graphite layers exfoliate and crumble, destroying the battery’s cycle life.

This geometric limitation is why sodium-ion batteries didn’t take off alongside lithium in the 1990s. The industry needed a new parking garage.

Enter Hard Carbon

The European breakthrough depends entirely on the perfection of “Hard Carbon” (non-graphitizable carbon). Unlike the orderly, stacked sheets of graphite, hard carbon is a chaotic mess of curved, disordered graphene sheets. Think of graphite as a neat stack of printer paper, and hard carbon as a crumpled ball of paper.

This “house of cards” structure, technically known as a turbostratic structure, creates larger voids (nanopores) where the bulky sodium ions can sit comfortably.

While this is slightly lower than graphite’s theoretical maximum for lithium (~372 mAh/g), it is sufficient for commercial application. The innovation announced this week involves synthesizing this hard carbon from local bio-mass, specifically lignin, a waste product from the Nordic paper and forestry industry, rather than importing specialized petroleum pitch precursors. This closes the final loop in the supply chain.

By utilizing lignin, European manufacturers essentially turn trees into batteries. This creates a supply chain that is immune to blockade, sanction, or price manipulation. It transforms the battery industry from a mineral extraction game into a forestry and chemical processing game; areas where Europe historically excels.

The LFP Trap and the Way Out

For the last five years, the “budget” EV market has been dominated by Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) batteries. LFP is durable, safe, and cheaper than high-performance Nickel-Manganese-Cobalt (NMC) cells. However, LFP represents a strategic vulnerability for the European automotive sector:

- China owns the supply chain. China refines roughly 60-70% of the world’s lithium and completely dominates LFP cathode production. Even if a cell is assembled in Germany, the cathode powder likely came from a ship originating in Shanghai.

- LFP freezes. In sub-zero temperatures, LFP charging speeds plummet, and capacity drops significantly. This has been a major consumer complaint in Norway and Canada.

Sodium-ion solves both problems simultaneously.

The Cold Weather Advantage

Sodium electrolytes have higher ionic conductivity at low temperatures. While an LFP battery might lose 30-40% of its range at -20°C, a sodium-ion pack retains over 90% of its capacity. For drivers in Scandinavia and the Alps, this “lower energy density” battery might actually offer more real-world range in the dead of winter than its lithium counterpart. This performance characteristic alone warrants a dedicated vehicle segment.

The Cost Reality

The raw materials for sodium cells are ludicrously cheap. Sodium carbonate (soda ash) costs roughly $300 per ton. Lithium carbonate, even after the crash and recent rebound, trades in the $15,000 - $30,000+ range.

While the manufacturing costs are currently high due to lack of scale (the “learning curve” penalty), the bill of materials (BOM) for sodium-ion is structurally destined to be 30-40% lower than LFP. This cost floor is critical for producing the elusive $20,000 electric vehicle—a price point that Western automakers have abandoned to Chinese competitors like BYD.

The Catch: Density vs. Destiny

If sodium technology is so superior, why are drivers not all using salt-powered cars today? The answer is simple: Weight.

Current commercial sodium-ion cells hover around 140-160 Wh/kg. State-of-the-art LFP cells are pushing 160-175 Wh/kg. High-nickel NMC cells can exceed 250-300 Wh/kg.

You will not see a sodium-ion battery in a Porsche Taycan or a Lucid Air. The physics forbids it. To get 500 miles of range, a sodium pack would be too heavy for the chassis, destroying handling and efficiency. This chemistry is not a replacement for high-performance luxury vehicles.

But for a city car? For a delivery van that drives 80 miles a day? For a grid storage system where weight is irrelevant? Sodium is perfect.

The Geopolitical Context: Europe’s Critical Raw Materials Act

This technical breakthrough exists within a tense political framework. The European Union’s Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA) sets ambitious targets for domestic extraction and processing of strategic minerals by 2030. Lithium is on the “Critical” list. Sodium is not.

By shifting demand to sodium, European manufacturers can bypass the CRMA’s most difficult hurdles. They do not need to open controversial new lithium mines in Portugal or Serbia, which face stiff local opposition. They do not need to compete with American buyers offering IRA subsidies for Australian spodumene.

The sodium supply chain is boring, and boring is good. It relies on soda ash factories in Poland and paper mills in Sweden. It is a supply chain of existing industrial infrastructure, not speculative mining ventures. This resilience is the primary driver behind the investment from legacy players like Northvolt and new entrants like Altris.

Forward-Looking Analysis: The 2026 Shift

The production of domestic hard carbon anodes signifies that the region is moving from “research” to “resilience.” Industry analysts expect the following market shifts over the next 12 to 24 months:

1. The “Standard Range” Fork

Automakers will begin bifurcation of their lineups. “Long Range” models will stick with high-nickel lithium chemistries. “Standard Range” models, particularly for the B-segment (like the Renault 5 or VW ID.2), will quietly migrate to sodium-ion. Marketing teams will position this not as “cheaper technology,” but as “Winter Proof” technology. This branding pivot is essential to avoid the perception of sodium as a “second-class” option.

2. The Grid Storage Explosion

The most immediate impact won’t be on roads, but on the grid. Solar and wind farms need massive buffers. The December 18th announcement proves that Europe can build these buffers without increasing its trade deficit with China. Expect utility-scale tenders in 2026 to explicitly favor “non-critical mineral” chemistries, effectively a disguised subsidy for sodium projects. This allows utilities to deploy GWh-scale projects without competing with the automotive sector for lithium cells.

3. The Death of the 12V Lead-Acid

One overlooked application is the humble 12V starter battery. Sodium-ion is a drop-in replacement for lead-acid. It offers thousands of cycles instead of hundreds and eliminates lead toxicity. This is the “Trojan Horse” market where sodium will achieve scale before conquering the powertrain. CATL has already hinted at this transition, but a European-made alternative secures the supply chain for military and logistical vehicles where lead is heavy and lithium is too expensive.

The Verdict: Strategic Sovereignty

The “Salt Revolution” is not about beating lithium on spec sheets. It is about beating geopolitics with chemistry. The cell produced this week might not hold as much energy as a Tesla 4680, but it holds something far more valuable to European policymakers: Sovereignty.

As trade wars heat up and supply chains fracture, the ability to build a battery out of wood scraps and table salt might just be the ultimate strategic advantage. The era of the “infinite” lithium supply chain is over; the era of localized, chemistry-agnostic energy storage has begun.

🦋 Discussion on Bluesky

Discuss on Bluesky