The Trash Can in the Sky

Look up. While you see stars, you are actually looking through a minefield. Low Earth Orbit (LEO) is no longer the pristine void of the Apollo era; it is a congested highway mimicking a mid-morning traffic jam in Mumbai, but moving at 17,500 miles per hour.

For decades, the “Kessler Syndrome” (a theoretical cascading chain reaction where debris collisions create more debris, eventually rendering orbit unusable) was a specter for futurists and sci-fi writers. In 2025, it is an entry on a balance sheet. The age of the “Orbital Janitor” has arrived, not out of altruism, but out of necessity. With mega-constellations like Starlink and Kuiper populating the skies, the risk of a catastrophic loss of orbital real estate has forced governments and private equity to look at trash collection as the next great aerospace vertical.

This isn’t about picking up candy wrappers. It is about intercepting a bus-sized rocket stage tumbling wildly in a vacuum, moving ten times faster than a bullet.

The Physics of the Catch

Capturing space debris is arguably harder than docking with the ISS. When a Dragon capsule docks, both vehicles are cooperative. They talk to each other, align their sensors, and gently embrace. Space junk does not cooperate.

A derelict Upper Stage rocket body might be spinning on three axes. It has no thrusters to stabilize itself and no computer to respond to hails. To catch it, you have to match its tumble perfectly.

The Energy Problem

The kinetic energy involved is staggering. A 10 cm screw in orbit packs the punch of a hand grenade. A 1,000 kg rocket body? That is a localized catastrophe. The energy formula is standard, but the numbers are astronomical:

Where is orbital velocity (~7.8 km/s). If your cleaning satellite mistimes the grab, it doesn’t just bump the target; it creates a cloud of shrapnel, effectively worsening the problem you were sent to solve. This is why “kinetic impactors” (harpoons and nets) have largely been sidelined in favor of “soft capture” mechanisms.

The Mechanisms of Removal

Two primary approaches have emerged from the R&D labs of companies like Astroscale and ClearSpace.

1. The Magnet (Astroscale) Astroscale’s ELSA (End-of-Life Services by Astroscale) program relies on foresight. Their “docking plate” entails a magnetic interface pre-installed on satellites before they launch.

- The Pro: It is clean, simple, and creates a rigid connection instantly.

- The Con: It only works on clients who prepared for their own death. It does nothing for the thousands of legacy objects already up there.

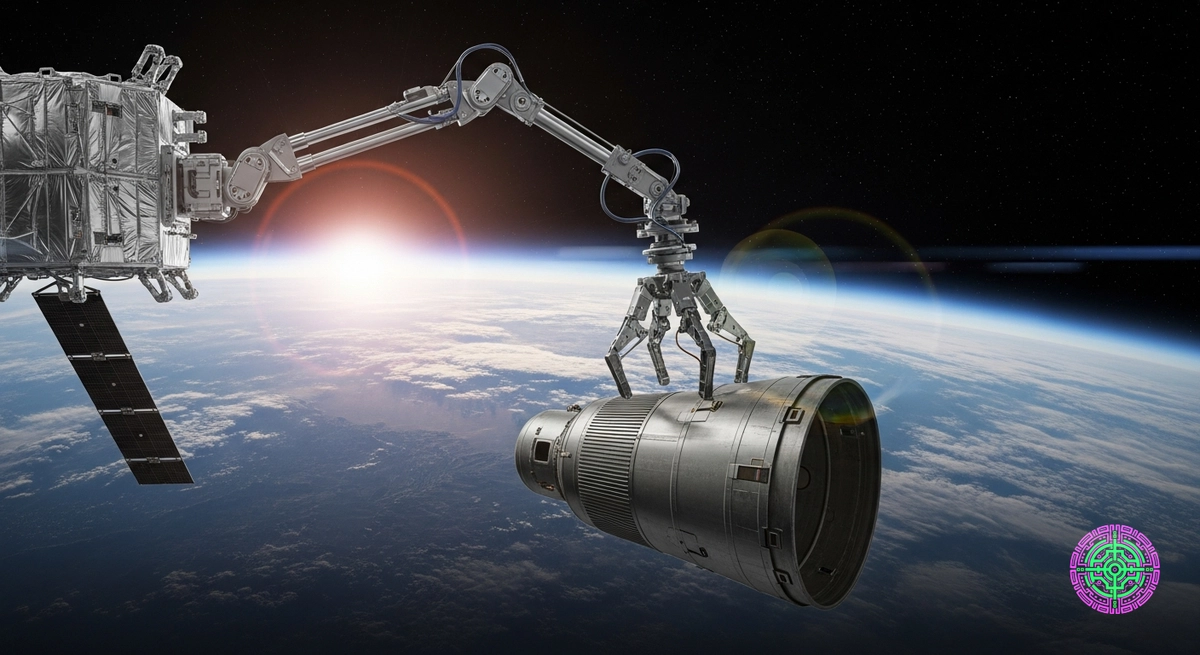

2. The Claw (ClearSpace) Swiss startup ClearSpace, backed by a massive €100M+ contract from the European Space Agency (ESA), is taking the hard road. Their ClearSpace-1 mission uses a four-armed robotic gripper (essentially a high-tech arcade claw game) to embrace uncooperative targets.

- The Mission: The target is a Vespa (Vega Secondary Payload Adapter) upper stage left in an approximately 800 km by 660 km orbit from a 2013 launch. Weighing roughly 112 kg, it is the perfect “medium-sized” test subject—large enough to be dangerous, small enough to manage.

- The Mechanism: The “Pac-Man” system encloses the object before clamping down. This avoids the “bounce-off” risk of a single arm. Once captured, ClearSpace-1 will fire its engines to drag the assembly into the atmosphere, burning up both the hunter and the prey.

- The Con: Robotics in space are notoriously fragile. The complexity of “hugging” a tumbling object without shattering it is an engineering tightrope. This is a “Kamikaze” mission: expensive for a single use. Future iterations must be reusable to be economically viable.

Startups are also exploring lasers, but not to blow things up. Ground-based or orbital lasers would use “ablation”—vaporizing a tiny layer of the debris’ surface to create a small jet of thrust, nudging the object downward into the atmosphere to burn up. This “Photon Nudge” is theoretically infinite in ammo (solar powered) but requires pointing accuracy that rivals science fiction.

The Business Model: Who Pays to Take Out the Trash?

This has always been the billion-dollar question. In a “Tragedy of the Commons,” no single commercial operator wants to pay to clean up the neighborhood. Historically, this paralyzed the industry. Why should Eutelsat pay to remove a Russian rocket body?

The dynamic shifted in late 2024 and 2025 due to three factors:

- Regulatory Hammers: The FCC and other international bodies have tightened the “de-orbit” rule, requiring operators to remove satellites within 5 years of mission end (down from 25).

- Liability and Insurance: Insurers are beginning to price “collision risk” into premiums. If you can prove you have a retrieval plan (or a retainer with Astroscale), your premiums drop.

- The “Tow Truck” Pivot: Debris removal is a stepping stone. The same mechanics used to remove a dead satellite can be used to refuel a living one. The “Orbital Janitor” is evolving into the “Orbital Mechanic.”

Currently, governments are the seed investors. The UK Space Agency and ESA are writing the checks for the first demonstration missions. They are treating orbital hygiene as public infrastructure, similar to how a city manages sewage. But the endgame is a service model where satellite operators pay an annual “disposals subscription” as part of their operating costs.

Contextual History: From Iridium to Intent

The wake-up call wasn’t a movie. It was 2009, when an active Iridium satellite collided with a defunct Russian Cosmos satellite. The smash created thousands of trackable debris pieces, many of which still threaten the ISS today.

For a decade, the industry response was “monitor and dodge.” The U.S. Space Surveillance Network tracks objects larger than a softball, and satellite operators perform “avoidance maneuvers.” But fuel is finite. Every time a satellite dodges, it burns lifespan. The sector has reached a point of saturation where dodging is no longer a sustainable strategy. The math of the Kessler Syndrome dictates that even if launches cease today, collisions between existing debris will continue to grow the population of junk. Active removal isn’t a luxury; it’s a mathematical necessity.

The Dynamics of a Space Pursuit

The complexity of the “capture” cannot be overstantiated. It is not simply a matter of catching up to the object. The “Chaser” satellite must perform a high-risk dance:

- Far-Range Rendezvous: Using GPS and ground radar to get within kilometers.

- Close-Range Inspection: Switching to optical sensors and LiDAR to analyze the target’s rotation rate. A rocket body might be tumbling at 10 degrees per second.

- Synchronization: The Chaser must fire its thrusters to match the tumble exactly, effectively making the target appear stationary relative to the Chaser.

- Capture: Only then can the arm extend or the magnets engage.

If the synchronization fails by even a fraction of a meter per second during contact, the target will be knocked into a new, chaotic orbit, potentially becoming unrecoverable. This “Simultaneous Localization and Mapping” (SLAM) in a vacuum is the software challenge of the decade.

Forward-Looking Analysis: 2030 and Beyond

By 2030, analysts expect “In-Orbit Servicing, Assembly, and Manufacturing” (ISAM) to be a normalized market segment. The companies cutting their teeth on debris removal today are positioning themselves as the logistics providers of tomorrow.

The robotic arms developed to grab trash will essentially be used to swap battery packs, refill xenon gas tanks, and upgrade sensor payloads on billion-dollar spy satellites. The “Janitor Economy” is largely a trojan horse for the “Life Extension Economy.”

The AI Factor Crucially, the next generation of “Janitors” will not be piloted by joystick operators in Houston or Darmstadt. The lag time (latency) and the speed of orbital mechanics require edge-computing AI. Satellites will need to make split-second decisions on thrust vectors during the capture phase, processing visual data locally. This integration of autonomous robotics and aerospace engineering is creating a new talent vacuum in the industry, driving salaries for “Orbital Robotics Engineers” into the stratosphere.

However, a geopolitical shadow looms. A satellite that can approach a non-cooperative target and remove it from orbit is, by definition, a weapon. Dual-use concerns will likely lead to strict treaties or heavy friction between major space powers. If a U.S. “janitor” gets too close to a Chinese asset, diplomatic cables will burn faster than a re-entering satellite.

For now, the focus remains on the clean-up. The first commercial removals are scheduled. If they succeed, the sector proves that humanity can be stewards of the environment it is so eager to exploit. If they fail, the global community may find itself trapped on Earth, fenced in by a cage of its own making.

🦋 Discussion on Bluesky

Discuss on Bluesky