The 400-Mile Mirage

Walk into any showroom in late 2025, and the marketing number that screams loudest is “Range.” The magic 400-mile (640 km) barrier, once the exclusive domain of six-figure luxury sedans, is now the standard target for mid-size SUVs and trucks. On paper, this looks like progress. It feels like the technology has matured.

But if you look closer at the spec sheets, a troubling correlation appears. The range isn’t increasing because the cars are getting smarter, more aerodynamic, or chemically superior. It is increasing because the cars are getting heavier.

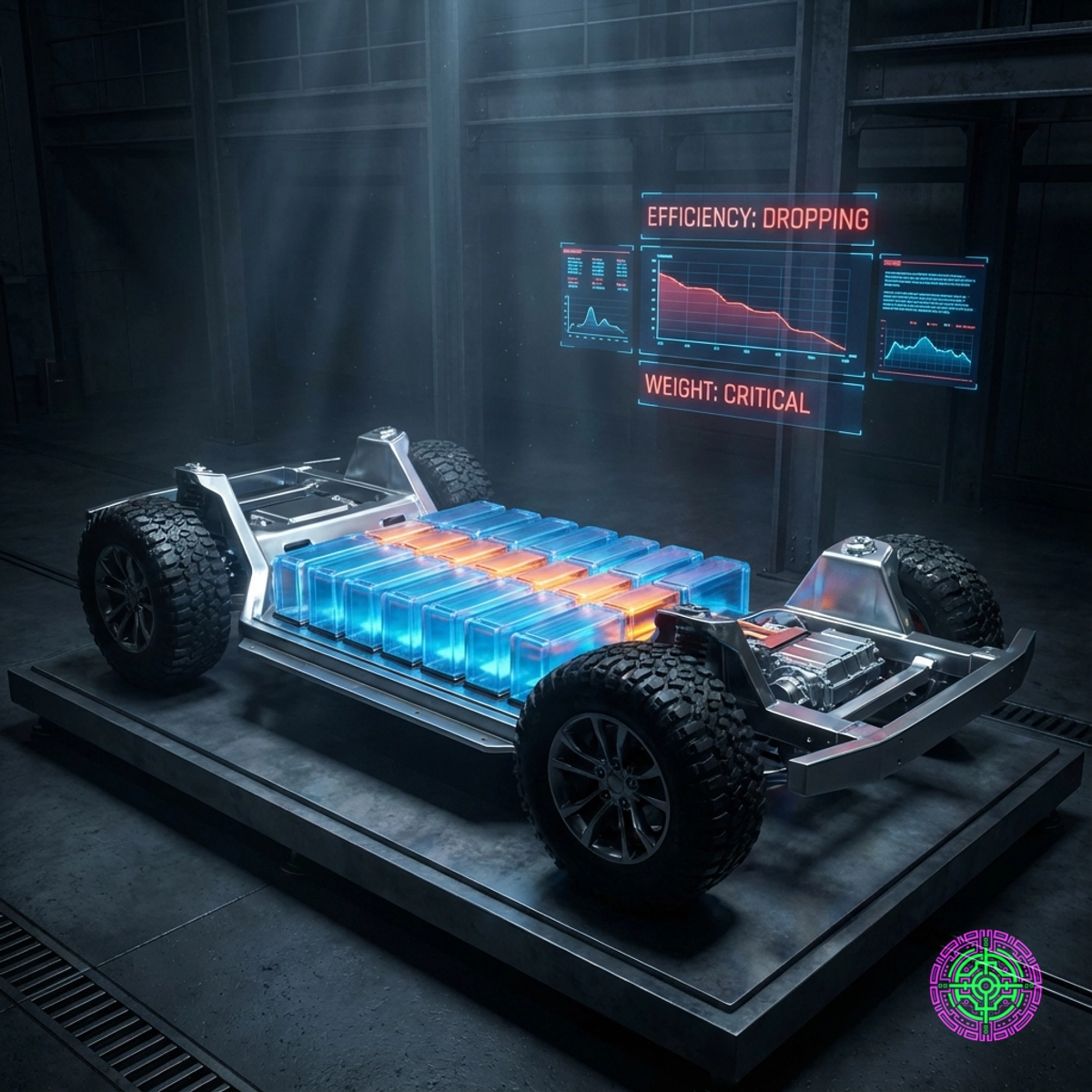

This is the “Range Bloat” trap. Instead of solving the difficult engineering challenge of efficiency (squeezing more miles out of every electron), automakers are solving the marketing challenge by simply stuffing massive, heavy battery packs into chassis that can barely support them. It is a brute-force approach to engineering, similar to solving poor fuel economy in a gas car by just installing a 50-gallon fuel tank. Driving range increases, but dead weight is dragged for 99% of the journey.

The data for the 2026 model year suggests that for the first time in the modern EV era, the median efficiency of new electric vehicles (measured in miles per kWh) is actually stagnating, even as range figures climb.

The Physics of the “Weight Spiral”

To understand why this is happening, one must look at the fundamental physics of electric mobility. The efficiency of an EV is largely determined by how much energy is required to overcome three main forces: aerodynamic drag, rolling resistance, and gravity (when climbing).

Rolling resistance () is directly proportional to the weight of the vehicle (, or normal force) and the coefficient of rolling resistance ():

As you add battery cells to increase range, you increase (weight). But it’s not a linear trade-off. It’s a spiral.

- More Range Needed: Marketing demands 450 miles instead of 350.

- Bigger Battery: Engineers add 30 kWh of capacity.

- More Weight: The pack gains 400 lbs (180 kg).

- Structural Reinforcement: The chassis must be beefed up to support the heavier pack. Brakes must be larger to stop it. Suspension components must be thicker.

- Secondary Weight: The vehicle gains another 150 lbs of structural steel and aluminum.

- Efficiency Drop: The heavier vehicle now consumes more energy per mile due to increased rolling resistance and inertia.

- Loop: To hit the original range target with this lower efficiency, you need even more battery.

This is why vehicles like the 2025/2026 electric trucks weigh in at over 8,000 or even 9,000 pounds. They carry battery packs exceeding 200 kWh (enough energy to power a typical American home for a week) just to achieve a highway range that a 1990s sedan could hit with a 12-gallon tank of gas.

The “Efficiency per Pound” Metric

The most damning metric is “Efficiency per Pound.” Let’s look at the divergence in the market.

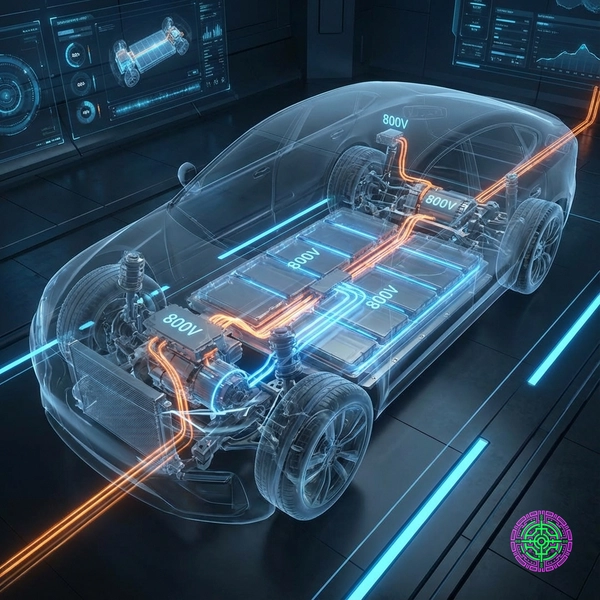

On one side, you have the “Lightweight Philosophy,” best exemplified by Lucid and efficient Tesla models. A Lucid Air Pure (2025/2026 specs) might achieve 4.5 to 5.0 miles/kWh. It hits a 400-mile range with a battery pack closer to 85-90 kWh.

On the other side, you have the “Brute Force” philosophy. Vehicles like the electric Silverado or the Hummer EV architecture (housed on the Ultium platform) achieve range not through finesse, but through mass. They might achieve 1.5 to 2.0 miles/kWh. To get 400 miles, they need a battery pack over 200 kWh.

The difference in raw material usage is staggering. You could build two and a half highly efficient EVs with the battery cells used in one inefficient truck. In a world where lithium and nickel supply chains are the primary bottleneck, this allocation of resources is arguably irresponsible.

The Hidden Costs of Weight Creep

The consequences of Range Bloat extend beyond just poor energy consumption. There are physical externalities that affect every road user.

1. Tire Emissions and Road Wear

Exhaust emissions are zero, but “non-exhaust emissions” are rising. Heavier vehicles shred tires faster. As the tire rubber grinds against the asphalt, it releases particulate matter ( and ) into the air and microplastics into the waterways.

A study by Emissions Analytics found that tire particulate wear from a heavy EV can be worse than the exhaust particulate emissions from a modern gas car (which has particulate filters). When an EV weighs 30% more than its gas counterpart, tire wear increases non-linearly.

Furthermore, road damage follows the Fourth Power Law:

If you double the weight on an axle, you don’t do twice the damage to the road surface; you do 16 times the damage. A fleet of 9,000-lb EVs will degrade municipal infrastructure significantly faster than a fleet of 3,500-lb crossovers, leading to massive future tax burdens for road repair.

2. Safety and Kinetic Energy

Kinetic energy () scales linearly with mass but with the square of velocity:

However, in a crash, mass () is the defining variable for the force transferred to the other object (momentum conservation). If a 9,000-lb electric truck collides with a 3,000-lb compact car, the physics are unforgiving. The crumble zones of the lighter vehicle are overwhelmed by the sheer mass of the heavier one. The “arms race” for range is inadvertently fueling an arms race for size, making roads more dangerous for pedestrians and drivers of smaller vehicles.

Why Lightweighting Stalled

Why are breakthroughs in lightweighting stalling?

1. The Density Plateau: The industry is currently in a transition period. The theoretical promise of Solid State Batteries (SSB) suggests double the energy density (less weight for same range). However, commercial scaling of SSBs has been slower than predicted. In 2026, most mainstream EVs still use liquid electrolyte Li-ion (NMC or LFP). LFP (Lithium Iron Phosphate), while cheaper and safer, is actually heavier per kWh than NMC. As automakers switch to LFP to cut costs, weights go up.

2. The Gigacasting Paradox: Tesla’s move to “Gigacasting” (casting huge sections of the frame as single pieces) was supposed to reduce weight. And it does, relative to hundreds of stamped parts. But automakers have used these weight savings to… you guessed it, add more battery. The weight saved in the chassis is immediately spent on more range.

The Missing Metric: Miles per kWh

Consumers have been trained to look at “EPA Range” as the single most important number. This needs to change. The metric that matters for your wallet and the grid is Miles per kWh (or Wh/mi).

- 3.5 - 4.0+ mi/kWh: Excellent efficiency. This vehicle is well-engineered.

- 3.0 - 3.4 mi/kWh: Average.

- Below 2.5 mi/kWh: Poor efficiency. You are driving a brick.

Charging speed is also a function of efficiency. An efficient car adds miles faster because it needs fewer electrons to go the same distance. If Car A gets 4 mi/kWh and Car B gets 2 mi/kWh, a 250 kW charger adds range to Car A twice as fast as Car B, assuming the charging curve allows it.

The Path Forward

The “Range Bloat” era, where dimensions and mass simply increase, is a temporary developmental cul-de-sac. The real next generation of EVs, arriving closer to 2027/2028, will likely pivot back to efficiency as the primary driver.

Technologies like Silicon Anodes (which swell but offer higher density) and Structural Battery Packs (where the cells are the frame) are the real answer. Companies like BMW with their “Neue Klasse” platform are explicitly targeting a 30% efficiency gain, acknowledging that just adding more cells is a dead end.

Until then, when you shop for a 2026 EV, don’t just look at the total range. Look at the curb weight. If a sedan weighs as much as a box truck, ask yourself if you really need to carry that extra ton of metal for the two days a year you drive 400 miles without stopping.

🦋 Discussion on Bluesky

Discuss on Bluesky