The yellow hatchback sitting on the docks in Shenzhen is more than just a car. It is a mathematical impossibility for the American automotive industry. The BYD Seagull, selling for roughly $9,500 (69,800 CNY) in its home market, represents the single greatest threat to Detroit since the 1970s oil crisis.

In response, Washington has built a wall. As of January 2026, the United States has finalized a 100% tariff on Chinese Electric Vehicles (EVs). On paper, this is a populist victory: a shield for the United Auto Workers (UAW) and a stay of execution for legacy giants like Ford and General Motors (GM). But in the cold light of global economics, these tariffs are not a shield. They are a “Detroit Fortress” that is hollowing out American competitiveness from the inside.

The Math of the Seagull

Detroit’s current strategy is to build “bigger is better” electric trucks and luxury SUVs that cost an average of $53,300. Meanwhile, BYD has mastered the art of vertical integration. Unlike American OEMs (Original Equipment Manufacturers) that outsource vast chunks of their supply chain, BYD produces its own Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) Blade batteries, electric motors, and even its own semiconductors.

This verticality allows for a cost structure that is 30% to 40% lower than Western rivals. The 2026 Seagull features a 30 kWh to 43.2 kWh battery, providing a range of up to 405 km (CLTC). For a person living in a city, that is not just “enough” range; it is more than a typical driver will use in a week of commuting.

Interestingly, BYD is losing its “home field advantage” as 2026 begins. A new 5% purchase tax in China and a shift toward percentage-based subsidies—favoring more expensive premium models over budget hatchbacks—are putting pressure on the Seagull’s domestic margins. This policy shift is likely to accelerate BYD’s international push, as the company seeks higher-margin markets to offset the cooling Chinese budget segment.

The core problem is American “regulatory capture” and the insistence on protecting high-margin internal combustion engine (ICE) products. By keeping a $10,000 EV out of the market, the policy does not just protect American jobs; it protects a high-price status quo that forces people into massive debt for a basic necessity.

The 1980s Japan Replay

History is rhyming, and Detroit should know the tune. In the 1980s, the US imposed Voluntary Export Restraints (VER) on Japanese cars. The goal was to give American makers time to build fuel-efficient small cars. Instead, the fortress allowed US makers to continue building gas-guzzling land yachts, while forcing Japanese companies like Toyota and Honda to build high-margin luxury brands: Lexus and Acura.

The 2026 tariffs are repeating this pattern. By blocking BYD’s cheap exports, the US is forcing the company to build massive factories in Mexico, Turkey, and Brazil. The “Electric Wall” is already being bypassed. When BYD’s Mexican-made EVs start crossing the border with United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) compliant parts, the 100% tariff will look like a sieve.

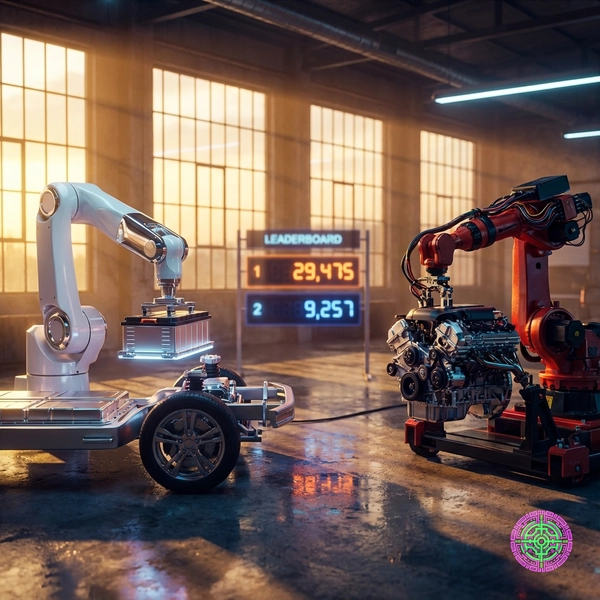

The Technical Deep Dive: Vertical Moats

Why can’t GM simply build a Seagull? The answer lies in the physics of the supply chain. Most American EVs are “assembly projects.” A manufacturer buys cells from LG, software from a third party, and motors from a specialist. Each layer adds a profit margin for the supplier.

By contrast, BYD’s Blade Battery energy density of approximately 150 Wh/kg is optimized for safety and cost. Because the company owns the lithium mines and the refining process, it bypasses the commodity price spikes that bankrupt smaller players. Furthermore, BYD uses a “Cell-to-Body” (CTB) architecture, where the battery is integrated into the vehicle’s frame. This reduces weight and part count, lowering the manufacturing cost in a way that legacy “skateboards” cannot match.

The math looks like this: If is the total cost of an EV: Where is the battery, is the powertrain, is the software, and is manufacturing. For BYD, the company captures the margin on all four variables. For a Detroit maker, the firm only captures the margin on and portions of .

The Geopolitical Feedback Loop

Protectionism creates a dangerous feedback loop. When a domestic industry is shielded from superior competition, the incentive to innovate disappears. Instead of matching the engineering efficiency of the Chinese LFP supply chain, American companies are doubling down on “luxury” EVs that the average person cannot afford.

This creates a “Green Cold War” where the US and China are not just competing on products, but on two entirely different economic philosophies. China is treating EVs as a commodity, similar to a smartphone or a toaster. The US is treating them as a luxury lifestyle choice. As long as this gap exists, the 100% tariff is merely a bandage on a sucking chest wound.

The Galapagos Effect

Biologists use the term “Galapagos Effect” to describe species that evolve in isolation, becoming perfectly adapted to a small island but completely unequipped to survive anywhere else.

The US auto market is becoming a Galapagos island. While the rest of the world, including Southeast Asia, Latin America, and even parts of Europe, adapts to the $15,000 high-tech EV, Detroit continues to iterate on the $70,000 electric pickup. Even the “entry-level” models in the US, like the Ford F-150 Lightning, struggle to stay below $50,000 for the Pro trim, while premium versions like the Silverado EV easily soar into the $75,000 to $95,000 range.

When American makers try to export these vehicles to global markets, the products are often rejected. The vehicles are too heavy, too expensive, and the software interface feels like a relic from 2012. This tension is visible in the recent Ford + Renault EV alliance, which represents an attempt by Western giants to co-develop a €20,000 platform just to stay relevant.

The Material Interests: Who Realizes the Profit?

Official narratives claim these tariffs protect the worker. However, the lobbying trail suggests a different focus. The UAW is fighting for the status quo because current contracts are tied to ICE and hybrid production lines. Ford and GM are fighting for the status quo because their dividends depend on the $15,000 profit margin they make on every large truck or SUV.

The loser is the American commuter, who loses access to affordable, reliable technology to satisfy the material interests of the “Detroit Fortress.” By the time the walls finally crumble, as history suggests they eventually will, Detroit will likely be unprepared. It will be the 1970s all over again, but this time, the cars will not be burning gasoline; they will be burning through what remains of the American industrial legacy.

The BYD Seagull is a warning. Economics cannot be easily ignored by trade policy. Detroit needs to stop building walls and start building better cars. Otherwise, the fortress they have built will eventually become their tomb.

🦋 Discussion on Bluesky

Discuss on Bluesky