In the high-stakes poker game of Artificial Intelligence, chips aren’t just silicon—they are credit.

For the past two years, the AI revolution has been fighting gravity. While demand for compute is infinite, the cost of capital has been punishing. With the Federal Reserve holding interest rates at multi-decade highs, the “AI Gold Rush” was effectively a cash-only game. Only the Hyperscalers (Microsoft, Google, Meta, Amazon) with their fortress balance sheets could afford to play, burning through cash reserves at an unprecedented rate.

But the game just changed.

With the Federal Reserve officially delivering the pivotal December 2025 rate cut, the economic logic of the AI buildout has fundamentally shifted. The market is moving from “Phase 1” (Cash-Financed Hyperscale Expansion) to “Phase 2” (Debt-Financed Industrial Buildout).

This specific 25-basis-point drop is the difference between a stalled revolution and a $1 Trillion infrastructure boom.

The $1 Trillion Problem: The Cash Flow Trap

To understand why rate cuts matter, you first have to understand the sheer terrifying scale of the bill.

In 2025, the combined capital expenditure (CAPEX) of the “Big 4” hyperscalers is projected to exceed $300 Billion. To put that in perspective, that is roughly the GDP of Portugal: spent on servers, concrete, and copper in a single year.

But the scarier metric is the “Cash Flow Consumption Rate.”

The “60%” Metric

Recent analysis shows that for major tech players, AI-related CAPEX is now consuming roughly 60% of operating cash flow, with some outliers pushing even higher.

When CAPEX consumes the majority of Operating Cash Flow, the “Free Cash Flow” cushion that Big Tech is famous for begins to erode. This is the “Cash Flow Trap.” Even highly profitable companies are finding themselves cash-constrained because every dollar earned is immediately reinvested into Nvidia H200s and liquid cooling systems.

For the past 18 months, these companies have been funding this out of their own pockets. But that math doesn’t scale forever. To reach the projected $1 Trillion annual investment needed for AGI (Artificial General Intelligence), the industry must tap the debt markets.

And that is where the Federal Reserve comes in.

Phase 2: The Debt Unlock

When the Fed Funds Rate was sitting at 5.5%, the cost of corporate debt was pushing 7% or 8%. For a massive infrastructure project with a 10-year payoff period, that hurdle rate is lethal.

A data center is, financially speaking, a “bond with upside.” You build it for a fixed cost (say, $1 Billion), and it pays you a yield (rent from compute usage) over 15 years.

If your cost of borrowing is 8%, and the data center yields 10%, your margin is razor-thin. The risk isn’t worth it. But if the cost of borrowing drops to 4.5%? Suddenly, the spread widens. The project goes from “risky” to “highly profitable.”

This is known as the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) unlock.

The “NeoCloud” Survival

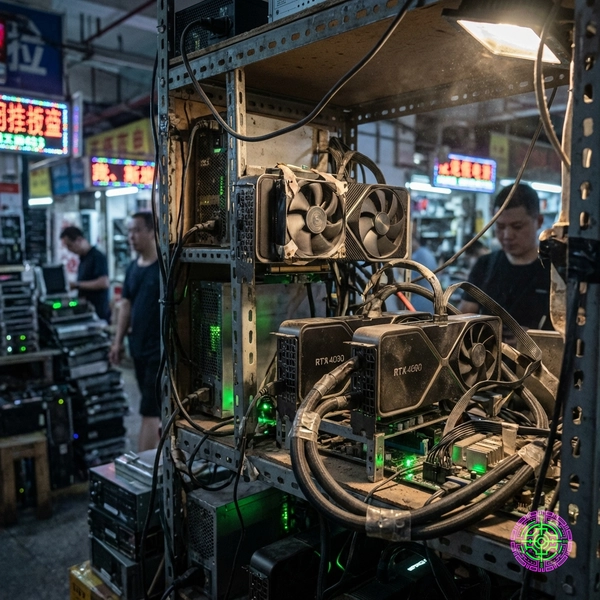

This is particularly critical for the “NeoClouds”—the smaller, specialized AI cloud providers like CoreWeave, Lambda, and Vultr. Unlike Google, they don’t have $100 Billion in the bank. They rely entirely on debt financing (often collateralized by the GPUs themselves).

At 8% rates, their business model is fragile. At 4%, it becomes a money-printing machine. The December 2025 cut was essentially a bailout for the mid-tier AI ecosystem, allowing them to refinance expensive debt and keep buying chips.

Technical Deep Dive: The “Return on Compute”

Why are companies willing to take on this debt? Because of a new economic metric: Return on Compute (RoC).

In traditional manufacturing, you measure Return on Assets (ROA). In the AI era, RoC is the governing law. The thesis is that a dollar spent on compute today generates more than a dollar of economic value in the form of intelligence, efficiency, or new software capabilities.

However, RoC is time-sensitive. A GPU purchased today is valuable. A GPU purchased three years from now is obsolete.

In this formula, is the interest rate. As falls, the Present Value of those future cash flows rises mathematically. This is why “Duration Assets”—assets that pay off over a long time, like bridges, tunnels, and data centers—are the most sensitive to interest rates.

But there is a second layer to this math: The Refinancing of the Upgrade Cycle. AI hardware depreciates faster than almost any other industrial asset. An Nvidia H100 bought in 2023 is already being eclipsed by the Blackwell B200 in 2025. This creates a “Capital Treadmill.” Companies must constantly borrow to upgrade their fleets just to stay competitive. At 8% interest, this treadmill is a death spiral. The cost of debt consumes the profit from the previous generation of chips before they can pay for themselves. At 4% interest, the math stabilizes. Companies can finance the purchase of B200s using 5-year notes, spreading the cost over the useful life of the asset. This aligns the “Liability Duration” with the “Asset Duration,” a fundamental principle of corporate finance that was broken during the high-rate regime. By cutting rates, the Fed has technically fixed the broken balance sheet of the entire AI training industry, allowing it to transition from a “Cash Burn” model to a sustainable “Asset Financing” model.

Contextual History: The “Fiber Bubble” Parallels

History doesn’t repeat, but it rhymes. The closest parallel to the 2025 AI CAPEX boom is the Telecommunications Boom of 1996-2000.

During that period, cheap capital fueled a massive buildout of fiber optic control cabling. Companies like WorldCom and Global Crossing borrowed billions to lay glass across the oceans.

- The Similarities: Massive upfront costs, debt-financed expansion, belief in “infinite demand” (for bandwidth then, for compute now).

- The Difference: In 2000, the demand for bandwidth hadn’t actually arrived yet. The pipes were empty. In 2025, the data centers are full before they are even built. The backlog for Blackwell chips is 12 months long.

The risk today isn’t that the industry is building “bridges to nowhere.” The risk is that the cost of the bridges (due to inflation and energy shortages) is rising faster than the rent charged.

The Winners and Losers: A Stock Picker’s Guide

This shift from Cash-Financed to Debt-Financed expansion creates a specific set of winners and losers in the public markets. The rising tide does not lift all boats equally; it lifts the boats with the most debt capacity.

The Winners: “The Leveraged Builders”

- The NeoClouds (CoreWeave, Lambda, etc.): These private companies (and their future public listings) are the biggest beneficiaries. Their entire existence depends on the spread between the cost of debt and the yield on compute. A 200-basis-point drop in rates effectively doubles their potential profit margin.

- Nuclear & Utility Stocks (OKLO, CCJ, Vistra): As the market moves to Phase 2, the bottleneck shifts to energy. These companies have massive CAPEX needs of their own to build SMRs (Small Modular Reactors). Lower rates allow them to finance these 10-year construction projects that were impossible at 7% rates.

- Digital REITs (Equinix, Digital Realty): These Real Estate Investment Trusts are highly sensitive to interest rates. Lower rates reduce their borrowing costs and increase the valuation of their existing properties. They become the “Landlords of the AI Age.”

The Losers: “The Cash-Rich Incumbents”

Paradoxically, the massive cash piles of Apple, Google, and Microsoft become slightly less of a competitive moat. When capital was expensive, their cash was a superweapon. No one else could afford to build. Now that capital is cheap, competitors can borrow to build. The moat narrows. While they will still dominate, the barrier to entry for challengers has effectively been lowered by the Federal Reserve.

Forward-Looking Analysis: The 2026 Energy Cliff

While cheap money solves the capital bottleneck, it exacerbates the physical bottleneck: Energy.

Cheap loans mean more shovels in the ground. More shovels mean more demand for copper, steel, and most importantly, megawatts. By making it easier to finance data centers, the Fed is inadvertently accelerating the collision with the “Energy Cliff”: the point where the U.S. power grid simply runs out of spare capacity.

The Prediction: As capital becomes abundant in 2026, the premium will shift from “Access to Cash” to “Access to Power.” Analysts expect to see:

- Private Power Grids: Tech giants effectively becoming utility companies, financing their own SMRs (Small Modular Reactors) and solar farms.

- The “Power Premium”: Real estate with a grid connection will trade at a 50x multiple compared to unconnected land.

- The Rise of “Sovereign AI” Debt: Nations issuing sovereign bonds specifically to fund domestic AI compute clusters, taking advantage of lower global rates.

The Verdict

The Federal Reserve’s pivot is not just a monetary event; it is an industrial one. By lowering the cost of capital, they have removed the last governor on the AI engine.

The $1 Trillion CAPEX wall is no longer an insurmountable barrier. It is just a financing detail. The check has been signed. Now, the industry must build it.

🦋 Discussion on Bluesky

Discuss on Bluesky