On January 29, 2026, Meta shocked Wall Street by guiding its 2026 capital expenditures to a staggering $115–135 billion. This figure represents nearly double its spend from just two years prior. The following day, Microsoft posted numbers that sent its stock tumbling, not because they missed revenue, but because investors finally asked the trillion-dollar question: “Where is all this money actually going?”

The official narrative is “capacity.” The CEOs differ only in the magnitude of their bullishness. But if you look past the earnings call slides and into the physical supply chain, you find a quieter, more terrifying reality. The chips are being bought, yes. But they are not being turned on.

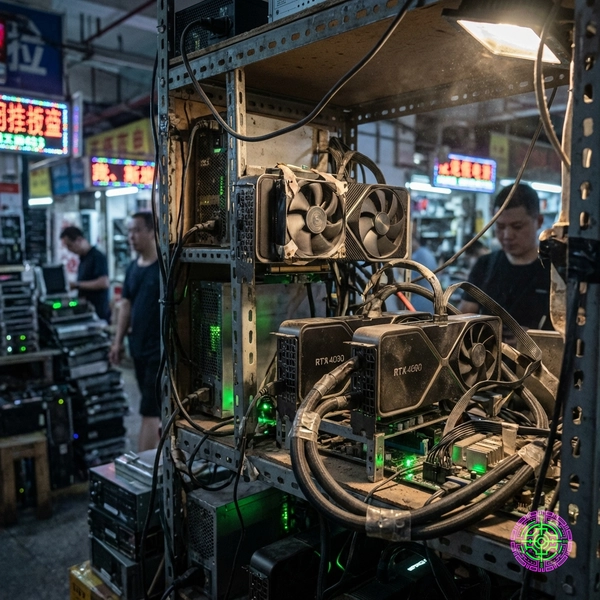

The industry is witnessing the birth of “Dark Silicon”: a massive accumulation of cutting-edge computation hardware that is sitting in warehouses, un-racked and un-powered, depreciating rapidly while waiting for a grid that cannot support it.

This is not a shortage crisis. It is a frighteningly exact replay of the 2001 “Dark Fiber” glut, only this time, the stranded asset isn’t glass in the ground. It is silicon in a box.

The Physics of a $700B Jam

To understand why “Dark Silicon” is inevitable, you have to look at the mismatch between two timelines: Silicon Velocity vs. Infrastructure Velocity.

The Velocity Mismatch

Nvidia and TSMC have performed a miracle. They have successfully ramped the Blackwell architecture (B200/GB200) into mass production. As of Q1 2026, the bottlenecks in CoWoS (Chip-on-Wafer-on-Substrate) packaging have largely eased. The chips are flowing.

But a GPU is useless without a home. To “turn on” a Blackwell cluster requires three things that TSMC cannot manufacture:

- High-Voltage Transformers: Lead times are currently 18–24 months.

- Liquid Cooling CDUs: The shift from air to liquid cooling requires a complete retrofit of legacy data center shells.

- Grid Interconnection: In markets like Northern Virginia or Santa Clara, new 50MW+ load wait times exceed 3 years.

The result is a logistical pile-up. Hyperscalers are taking delivery of GPUs because they must. If they refuse a shipment, they lose their allocation slot for the next generation (Rubin). So they accept the pallets, pay the invoice, and store the hardware.

The Math of Stranded Assets

Let’s look at the density problem. A legacy data center rack consumes about 10–15 kW. A rack of Nvidia NVL72s consumes over 165 kW.

This isn’t a “plug and play” upgrade. It is a change in the fundamental physics of the building. You cannot simply put these racks in existing empty space.

When the Right side of that equation exceeds the Left, you get Dark Silicon. The chips exist, but the electrons do not.

From CoWoS to Power: The Bottleneck Shift

Throughout 2024 and 2025, the industry was obsessed with “packaging capacity.” Investors tracked TSMC’s CoWoS alignment as the primary constraint on AI growth. Companies like Amkor and ASE poured billions into packaging facilities, and by late 2025, the constraint broke.

The irony is that solving the packaging bottleneck merely accelerated the collision with the Power Wall.

When supply was constrained, Hyperscalers could receive chips as fast as they could deploy them. The trickle of supply matched the trickle of new power capacity. But now that the CoWoS dam has broken, the chips are flooding in faster than the utility companies can dig trenches.

This creates a dangerous inventory overhang. In 2024, a delivered GPU was plugged in the same week. In 2026, a delivered GPU might sit in a bonded warehouse for 9 months waiting for a transformer.

Echoes of 2001: The Fiber Glut

In the late 1990s, companies like Global Crossing and WorldCom laid millions of miles of fiber optic cable, convinced that internet traffic was doubling every 100 days. This was a myth driven by bad data, but the capital markets believed it. They spent hundreds of billions burying glass.

When the crash came in 2001, estimates suggested that 85% of that fiber was “Dark” - unlit, unused, and generating zero revenue.

The 2026 dynamic is hauntingly similar:

- The Myth: “Scaling laws are infinite” (Traffic doubling replaced by Parameter doubling).

- The Spend: Unprecedented Capex relative to revenue (Meta at 33% of revenue).

- The Glut: Inventory building faster than it can be deployed.

The difference? Fiber optic cable essentially lasts forever. It doesn’t rot. A spool of fiber buried in 2001 was still useful in 2010.

Silicon rots.

The Depreciation Bomb

This is where the accounting gets ugly. Under US GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles), an asset is typically depreciated over its “useful life.” For a server, that’s usually 3–5 years.

But for AI silicon, the “useful life” is dictated by the release cycle of the next chip. Nvidia operates on a roughly 18-month cycle. If a B200 GPU sits in a warehouse for 12 months waiting for a power hookup, it has lost two-thirds of its prime economic relevance before it ever computes a single gradient descent.

The “Placed in Service” Loophole

Corporations skirt this by classifying uninstalled hardware as “Inventory” or “Construction in Progress” (CIP) rather than “Property, Plant, and Equipment” (PP&E). Crucially, depreciation does not start until the asset is “placed in service.”

This creates a terrifying artifact on the balance sheet: Billions of dollars of “brand new” assets that are technically valued at 100% of purchase price, but are effectively obsolescing in a box.

In late 2026 or early 2027, when these chips are finally racked, they will be competing against the next generation (Rubin), which offers better performance-per-watt. The “Dark Silicon” will turn on, only to be immediately obsolete.

The Liquidity Trap

This accumulation depends on endless liquidity. If the “AI Revenue” doesn’t materialize to cover the depreciation, the cash flow crunch will be immediate.

Hyperscalers are currently paying for chips with cash generated from their core businesses (Ads, Cloud Services). But as the inventory pile grows, the Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) plummets.

When WorldCom collapsed, it wasn’t because fiber wasn’t valuable. It was because the debt service on the unlit fiber exceeded the cash flow from the lit fiber.

Microsoft and Meta are not WorldCom. They have fortresses of cash. But even a fortress can be drained by a $130 billion annual leak. If the AI revenue ramp is delayed by even 12 months due to grid constraints, the “Dark Silicon” drag on earnings will be visible to every algorithm on Wall Street.

The Boring Hypothesis: Why Not Just Wait?

The skeptical reader might ask: “Why don’t these smart CFOs just halt shipments until the data centers are ready?”

They can’t. The semiconductor market is a monopsony of fear. If Microsoft tells Nvidia “pause shipments for 3 months,” Nvidia sells those chips to Musk or Zuckerberg, and Microsoft loses its place in line for the next chip.

It is a Prisoner’s Dilemma. The optimal move for the group is to slow down. The optimal move for the individual is to hoard.

So they hoard.

The 2027 Reckoning

The industry is currently in the “Accumulation Phase.” The Capex numbers from Amazon ($134B) and Meta ($135B) confirm this. The market is viewing this spend as “deployment.” It is not relative to deployment. It is procurement.

The reckoning arrives when the auditors force a “Mark to Market” on that inventory, or when the efficiency gains of the next chip make the “Dark Silicon” energetically unviable to turn on at all.

If you are holding TSMC or Nvidia stock, you love the sales. But if you are holding the Hyperscalers, you are holding the bag. They are buying perishable fruit and storing it in a broken refrigerator.

By Q4 2026, look for a new term in the earnings calls: “Inventory Impairment.” That will be the sound of the bubble popping. Not with a bang, but with the quiet hum of a forklift moving obsolete pallets to the recycling center.

🦋 Discussion on Bluesky

Discuss on Bluesky