The experiment is over. After years of attempting to convince truck owners that stopping every 100 miles to charge when towing heavy loads was “part of the adventure,” Ford has officially pulled the plug on the all-electric F-150 Lightning.

In a stunning pivot announced this week, Ford officials confirmed that while the Lightning nameplate may survive, the pure battery-electric vehicle (BEV) architecture is being scrapped. Its successor will be an Extended-Range Electric Vehicle (EREV)—a truck driven by electric motors but carrying an onboard gas generator to recharge the battery on the fly.

The promise? 700 miles of total range and “uncompromised” towing.

“The typical customers will get through nine out of 10 days on electricity alone,” a Ford executive explained. “It will be able to tow with uncompromised range, which is significant for truck owners.”

This isn’t just a product change; it’s a concession to physics. Here is why Ford had no choice but to bring back the gas tank.

The Physics of Failure: Why Pure EV Trucks Can’t Tow

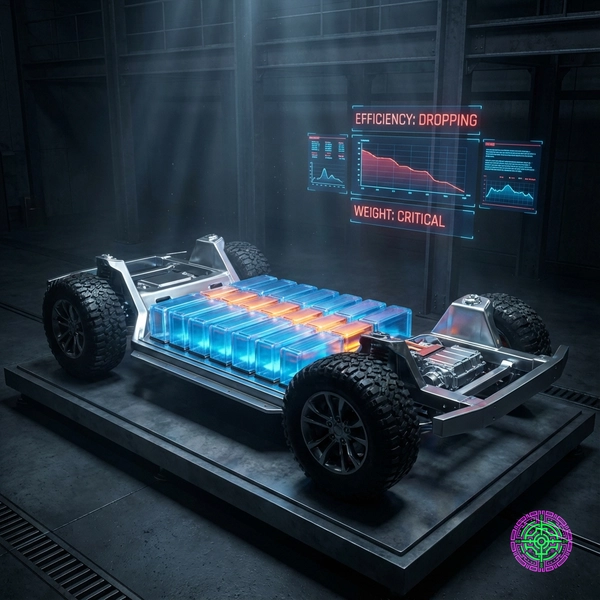

To understand why the Lightning failed as a work truck, you have to look at the energy density problem.

Passenger cars benefit from aerodynamics. Trucks do not. When you attach a 7,000 lb box trailer to a truck, aerodynamic drag becomes the dominant force consuming energy, often doubling or tripling consumption at highway speeds.

The Energy Density Math

- Gasoline: ~\12,000 Wh/kg

- Li-Ion Battery: ~250 Wh/kg

Gasoline is nearly 50 times more energy-dense by weight than current batteries. In a daily commuter car, this doesn’t matter much because the energy required to move a sleek sedan 30 miles is low. But towing a brick through the wind requires massive sustained power output.

When a standard F-150 Lightning tows a substantial load, its range drops from 320 miles to roughly 100-120 miles. For a contractor or someone towing a boat to the lake, this functional range anxiety makes the vehicle useless.

To achieve a “real” 300-mile towing range with a pure EV, Ford would need to essentially double the battery size to over 250 kWh. This would:

- Add thousands of pounds of “parasitic weight” (weight that consumes energy just to move itself).

- Push the truck’s price well over $100,000.

- Reduce payload capacity to near zero.

The EREV Solution: The Best of Both Worlds?

Ford’s new strategy mirrors the Ram 1500 Ramcharger, which recently debuted with a similar architecture. This is not a traditional hybrid.

In a traditional hybrid (like a Prius or F-150 PowerBoost), the gas engine connects mechanically to the wheels. In an EREV, the gas engine acts solely as a generator (genset). There is no mechanical linkage between the engine and the wheels.

How It Works

- Electric Drive: The wheels are always turned by high-torque electric motors, preserving the instant torque and smooth towing experience of an EV.

- The Battery: A smaller battery (likely 90-100 kWh instead of 131 kWh) provides ~100-150 miles of pure electric range for daily tasks like commuting or job site runs.

- The Generator: When the battery drops below a certain threshold (or when “Tow Mode” is engaged) a gas engine spins up to generate electricity, feeding the motors directly or recharging the battery.

This architecture solves the two biggest problems with electric trucks: Cost and Towing Range.

By shrinking the battery, Ford cuts roughly $10,000 to $15,000 out of the bill of materials. They then replace that cost with a cheap, mass-produced internal combustion engine. The result is a truck that drives like an EV but fuels like a diesel when it needs to work.

The “Project T3” Pivot

For years, Ford hyped “Project T3” (Trust The Truck) as its “Millennium Falcon,” a futuristic, dedicated EV platform. It now appears T3 has morphed into, or been usurped by, this EREV platform.

This pivot acknowledges a hard truth: Battery technology is not improving fast enough to beat gasoline’s energy density for heavy-duty hauling.

While solid-state batteries promise 500 Wh/kg in the laboratory, they are years away from mass production at automotive scale. Ford cannot afford to lose the truck market to Ram or GM’s Silverado EV (which is sticking to massive batteries for now) while waiting for a physics breakthrough.

The Competition: Ram Was Right

Ford is effectively admitting that Ram’s parent company, Stellantis, made the right call earlier. The Ram 1500 Ramcharger announced last year uses the exact same architecture Ford is now adopting, and the specs provide a preview of what the new F-150 will look like.

- Ramcharger Specs:

- Battery: 92 kWh (Liquid cooled)

- Generator: 3.6L Pentastar V6 (130 kW sustained output)

- Range: 690 miles total (145 electric + 545 gas)

- Towing: 14,000 lbs

If Ford targets “700+ miles,” they are clearly trying to one-up Ram’s 690-mile figure. Ideally, Ford will use a similar setup, perhaps pairing a ~90 kWh battery with a high-efficiency engine like the 2.3L EcoBoost or a naturally aspirated variant optimized purely for steady-state power generation.

The critical difference here is the generator size. The Ramcharger’s 130 kW generator is powerful enough to maintain highway speeds while towing even if the battery is depleted. This is the “secret sauce” of a towing EREV: the gas engine must be large enough to handle the continuous load, not just the average load.

The “Range Bloat” Trap

This shift also highlights a growing industry realization about “Range Bloat.” To make a pure EV truck tow 300 miles, you need a battery approaching 200+ kWh (like the Chevy Silverado EV’s projected pack).

This is a massive resource allocation inefficiency. A 200 kWh battery consumes enough Lithium, Cobalt, and Nickel to build:

- Two Ramcharger-style EREVs (90 kWh each).

- Four standard Model 3s (50 kWh each).

- Hundred mild hybrids (2 kWh each).

By putting a 200 kWh battery in a single truck that only uses 10% of that capacity for daily driving, the industry is technically wasting the world’s limited battery supply. The EREV approach is arguably more sustainable for this vehicle class: it electrifies 95% of the miles driven (the daily commute) without carrying thousands of pounds of “dead weight” battery capacity that is only needed for the annual road trip.

The $19 Billion Reality Check

The pivot comes with a hefty price tag. Ford announced a potential $19.5 billion write-down related to its EV investments. This is an admission that the capital poured into pure BEV plants and battery factories was misallocated based on overly optimistic adoption curves.

However, the stock market often rewards such “ripping off the band-aid.” By cutting losses on a product that consumers weren’t buying (the pure EV Lightning) and pivoting to a product they will buy (a 700-mile EREV), Ford is aligning its engineering with its customers’ wallets.

Is This the End of the Pure EV Truck?

Not necessarily, but it is the end of the general purpose pure EV truck.

Small, lifestyle electric trucks (like the Rivian R1T for camping or the Cybertruck for… whatever Cybertruck owners do) will use pure BEV architectures because their owners rarely tow heavy loads for 500 miles.

But for the “Work Truck” segment, the core of Ford’s business, the EREV is the superior engineering solution. It decouples power generation (gas) from power delivery (electric motors), allowing the engine to run at its peak efficiency RPM constantly, rather than revving up and down with traffic.

Ford’s decision to promise “700 miles” is a direct shot at the range anxiety that killed the first Lightning. By keeping the electric drive but bringing back the fuel tank, Ford is betting that truck buyers don’t actually care about “saving the planet” as much as they care about getting to the campsite without stopping for an hour in a Walmart parking lot.

They are almost certainly right.

🦋 Discussion on Bluesky

Discuss on Bluesky